Sport Nutrition and the Role of Dairy

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Give athletes a boost with exercise, milk and other dairy products

- 3. Key messages for the physically active

- 4. General facts about nutrients in sports nutrition

- 5. From facts to plate

- 6. Hype about hydration

- 7. Intake before exercise

- 8. Intake during exercise

- 9. Intake after exercise

- 10. Frequently asked questions and answers for athletes

- 10.1 How can a balanced diet enhance an athlete’s performance?

- 10.2 How can dairy products aid muscle recovery after sport?

- 10.3 What if an athlete needs to lose weight while training? (and a few words on intermittent fasting)

- 10.4 How can sports drinks support training or performance?

- 10.5 How should an athlete start a competition day?

- 10.6 Can the food at sports events be recommended for athletes?

- 10.7 What about supplements?

- 11. Sport nutrition programme checklist for coaches

- 12. Glossary

- 13. References

Sports Leaflet Download

1. Introduction

What athletes and players eat affects their performance, and appropriate food choices will affect how well they train and compete. Good food choices planned at the right time may have the biggest impact on training. A good diet can support consistent intensive training, optimise recovery and limit the risks of illness or injury. Good food choices can also promote adaptations to the training programme to ensure improvement in training and competition performance over time.

This booklet contains information that will help athletes and players at all levels of participation to make informed choices to meet their nutritional needs. Every athlete or player is different and there is no single diet that meets the needs of all athletes or players at all times. The booklet aims to give practical information against a blueprint of basic sports nutrition principles but is not intended as a substitute for individual advice from a qualified professional.

The booklet has been compiled as part of the Consumer Education Project (CEP) of Milk South Africa. The CEP would like to thank dietitians Nicki de Villiers and Lize Havemann-Nel for their input and sharing their years of experience in compiling this manual.

(This document is a general guideline for learners and athletes. For personal needs, consult a registered dietitian by visiting the website of the Association for Dietetics in Southern Africa at www.adsa.org.za.)

Background on the CEP

The CEP is an initiative of Milk South Africa that was formed to communicate health and nutritional messages regarding dairy products to consumers and health professionals in South Africa. The major objectives are to address the misconceptions and lack of information regarding the nutritional and health benefits of dairy products. The project requires expert knowledge from fields such as dietetics, nutrition, dairy technology, communication, and consumer behaviour. Through appropriate structures and processes the CEP makes use of experts in the different fields to create an integrated, multi-faceted communication campaign. ‘Good nutrition and physical activity go hand in hand.’

2. Give athletes a boost with exercise, milk and other dairy products

Physical activity promotes health and fitness. The benefits ascribed to physical activity include building and maintaining healthy bones, muscles and joints. Physical activity helps control weight, builds lean muscle, and reduces fat. It can also exert a positive effect on brain health, resulting in better memory and cognitive performance and reducing the symptoms of depression. Establishing an active lifestyle throughout the younger years can also prevent the risk factors contributing to various health conditions like heart disease, obesity and Type 2 diabetes.1,2

All adolescents and young adults benefit from physical activity. It is recommended that children and adolescents do 60 minutes or more of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity daily. Aerobic activity should make up most of the 60-plus minutes of physical activity each day. Muscle-strengthening activities such as gymnastics or push-ups should be included at least three days per week. Bone strengthening activities, such as skipping or running, should also be included three days per week as part of the recommended 60-plus minutes per day.1-3

Good nutrition and physical activity go hand in hand. Two main aspects of sports nutrition require attention: the quantity and quality of nutrients. The quantity of nutrients refers to sufficient intake of energy and optimal hydration. Quality implies the intake of high-quality nutrients like protein, calcium and other micronutrients.3

Dairy products are included in the South African food-based dietary guidelines. Milk, yoghurt, maas and cheese are good sources of calcium and protein, which are vital nutrients for bones and muscle mass maintenance. Young athletes can benefit from the inclusion of dairy products to aid in bone growth and mineralisation, which occur during infancy and childhood and lead to peak bone mass after early adulthood. A low peak bone mass can increase the risk for osteoporosis and fractures later in life. Milk, a complete food matrix, has an effect on bone and muscle health that is more than the sum of its nutrients.4

Low-fat flavoured milk and drinking yoghurt not only provide fluid but also contain calcium, protein, carbohydrates and electrolytes in an ideal combination to prevent dehydration and fatigue. Research has shown that athletes find it easier to recover from dehydration when carbohydrates are supplied through drinks that come in a variety of flavours. The intake of protein together with fluids has also been shown to be ideal to help muscles recover after exercise.

Athletes and players who take part in sport need three to four servings of dairy products a day (low-fat milk, low-fat yoghurt, maas and/or cheese).5-9

Low-fat flavoured milk or drinking yoghurt is the perfect sports drink because it:

- contains carbohydrates to boost energy, combat fatigue, fill up fuel stores and ensure hydration;

- contains protein to help muscles recover, giving a rich supply of easily absorbed calcium to build and maintain strong bones;

- contains potassium, sodium and magnesium to replace electrolytes lost through sweating;

- contains fluid to prevent heat stress and exhaustion; and

- comes in a variety of flavours to encourage youngsters to drink enough fluids.

3. Key messages for the physically active

- Diet affects performance.

The food that we choose in training and competition will affect how well we train and play/compete. - Every athlete is different.

No single diet will meet the needs of all athletes.

- An athlete’s diet may have its biggest impact during training.

A good diet will help support consistent, intensive training, promote optimal adaptation to training, and limit the risks of illness or injury.

- Getting the right amount of energy is key to staying healthy and performing well.

Excessive energy intake will increase body fat; insufficient energy intake will hinder performance and the ability to ward off illness and injuries. Food and beverages provide energy through nutrients.

- Carbohydrates supply the muscles and the brain with the fuels needed to meet the stress of training and competition.

Athletes should know when to eat which foods so that they can meet their carbohydrate needs.

- A balanced, varied diet will generally supply enough protein for building and repairing muscles.

Additional protein intake through protein supplements is hardly ever necessary.

- A varied diet that meets energy needs and is based largely on nutrient-rich choices should provide an adequate supply of vitamins and minerals. Athletes should include vegetables, fruits, beans, legumes, cereals, lean meats, fish and dairy products in their diets.

- Maintaining hydration is important for performance.

Appropriate fluid intake before, during and after exercise can help improve performance.

- Athletes should refrain from the indiscriminate use of dietary supplements.3

The foods and beverages that athletes consume will affect their performance during training and competition. Good food choices offer the following to athletes or players:

- Fuel to train and perform

- Optimum adaptation and gains from the training programme

- Enhanced recovery between workouts and events

- Achievement and maintenance of an ideal body mass and physique

- Reduced risk of injury, overtraining and illness

- Confidence in being well-prepared to face competition

- Optimal performance in their chosen sport or activity

- Enjoyment of food at social eating occasions at home, and during travel10

4. General facts about nutrients in sports nutrition

4.1  Energy

Energy

Energy intake sets the quantity (budget) from which an athlete must meet their needs for macronutrients (carbohydrate, protein and fat). At the same time, the quality and variety of foods to provide adequate amounts of micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) are equally important.3

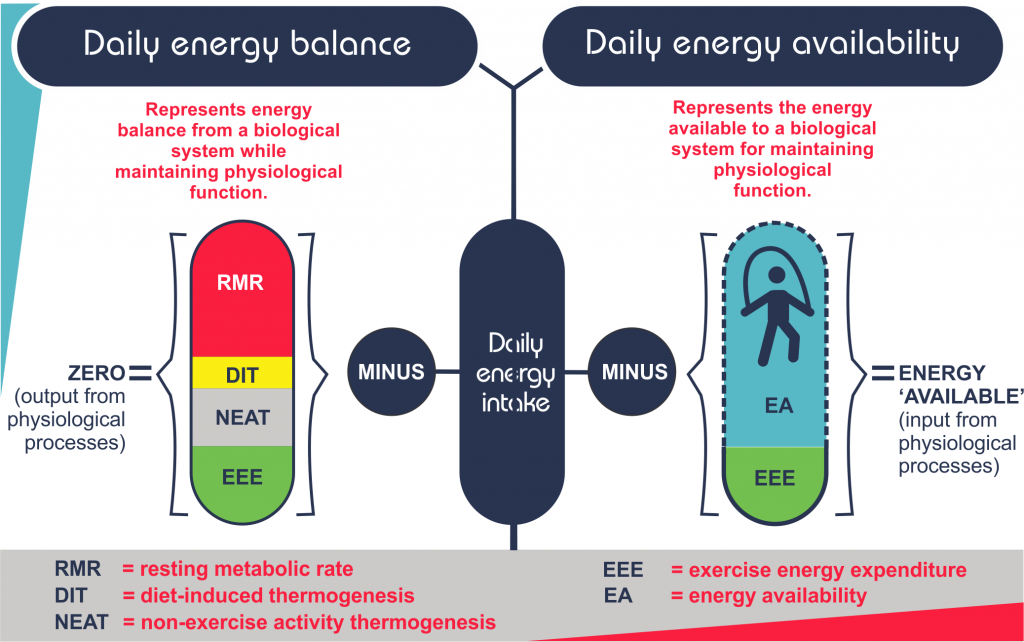

The energy needs of an athlete are determined by the baseline metabolic needs, growth and physical activity, and based on the intensity, duration and frequency of training sessions and competition. If the amount of food an athlete or player eats is equal to the energy expenditure, the athlete or player is said to be in energy balance.11

Energy availability, on the other hand, refers to the energy that is available to the body after the energy cost of physical activity has been deducted from the daily energy intake.11

The body can cope with a small drop in energy availability, but if it becomes too great, this will compromise its ability to undertake the processes needed for optimum health and functioning.11

Ideas for maintaining adequate energy availability

- Adjust energy intake according to training load. If you know that it is going to be a hard training week, eat more from the beginning of the week.

- Take care when there is a change in your food environment or eating pattern.

- Do not experiment with drastic diets that limit energy intake or food variety. Plan weight loss to happen at a slower rate.

- Seek expert help as soon as you develop stress related to food and body image.

- An interruption of the menstrual cycle in females needs further assessment and intervention.

- If you are unsure about your energy needs, consult a registered dietitian.11

NOTE: The consequences of low energy availability include irreversible loss of bone, as well as impairment of hormone, immune and metabolic function. It is not worth it!

4.2  Fuel foods

Fuel foods

Physical activity and sport involve muscle contraction. For the muscles to contract, energy is required and supplied through the food that we eat. Getting the right amount and type of fuel from food will help athletes train well and stay healthy.

Carbohydrates and fat are the preferred fuel sources for the working muscles, but carbohydrates are the main source of fuel.

Carbohydrate as fuel food

• Why should an athlete eat carbohydrates?

Carbohydrates are the main fuel source for athletes, especially during high-intensity activities such as running, cycling, and squash, and team sports such as hockey, soccer, and rugby. The body stores carbohydrates in the form of glycogen in the liver and muscles. Liver glycogen is important to maintain normal blood sugar levels during exercise, and muscle glycogen is important to fuel working muscles.12

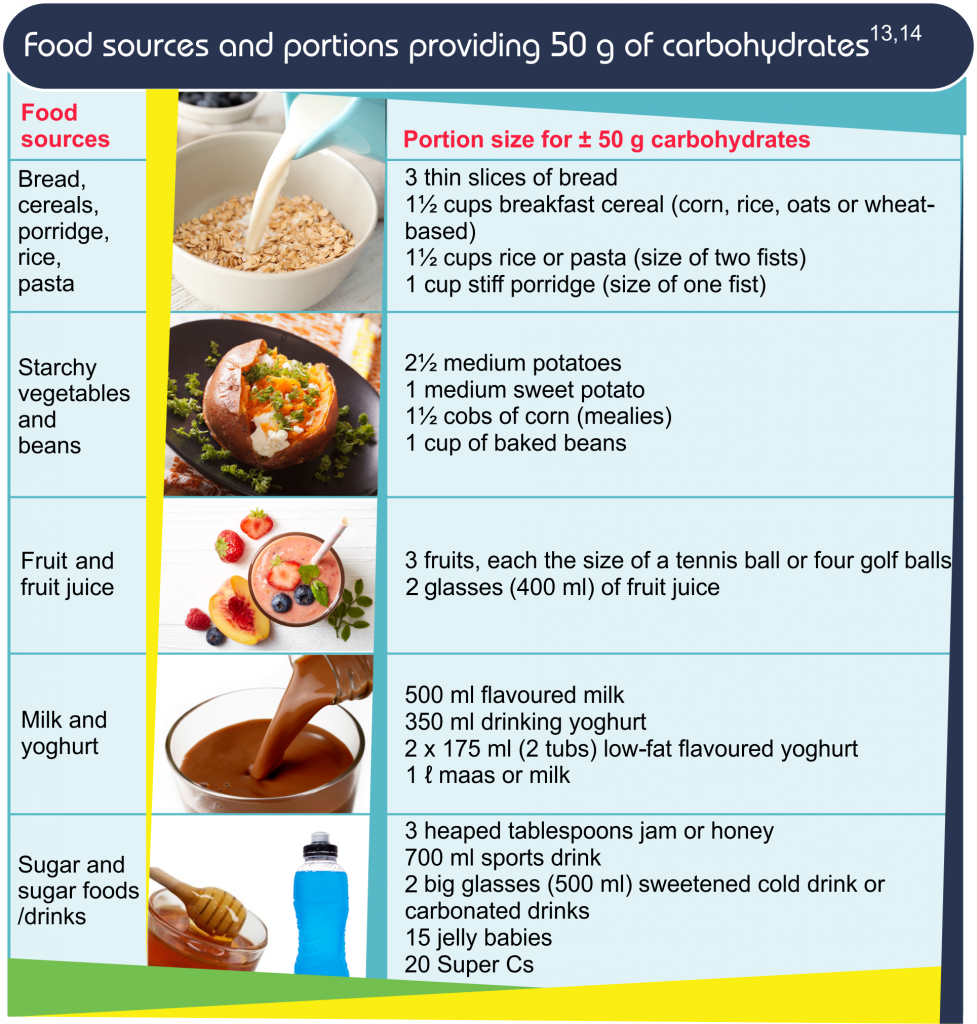

• Where can an athlete find carbohydrates?

Good nutritious sources of carbohydrates are starchy foods (e.g. bread, rice, pasta, couscous, maize meal porridge, and cereals), fruit (fresh and dried), fruit juice, starchy vegetables (e.g. potato, sweet potato, corn, and beetroot) and pulses (e.g. beans and lentils). Milk, flavoured milk and low-fat flavoured yoghurt are also good sources of carbohydrates and at the same time contribute to the athlete’s protein needs. Sugar and sugary foods and drinks such as sweets, Coke and sports drinks are also high in carbohydrates, and can be included as fuel sources during exercise.

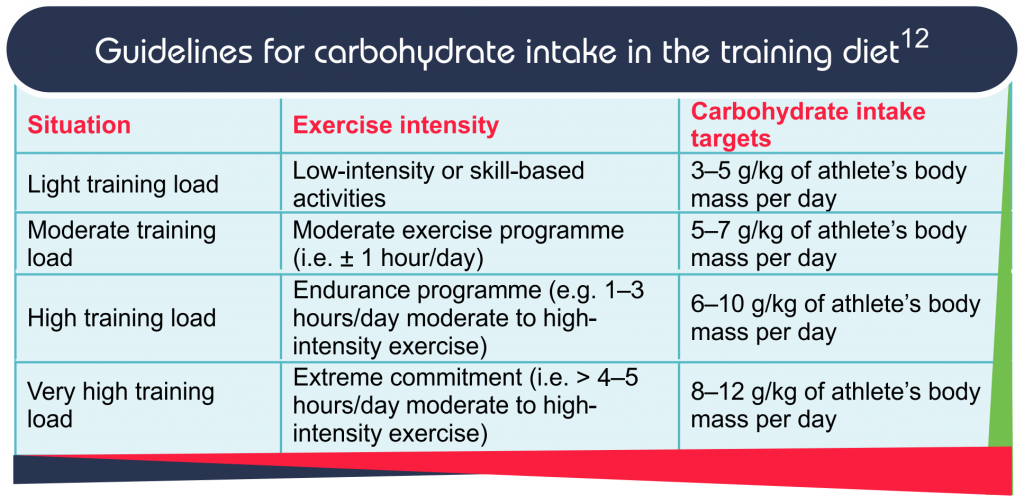

• How much carbohydrates do an athlete need?

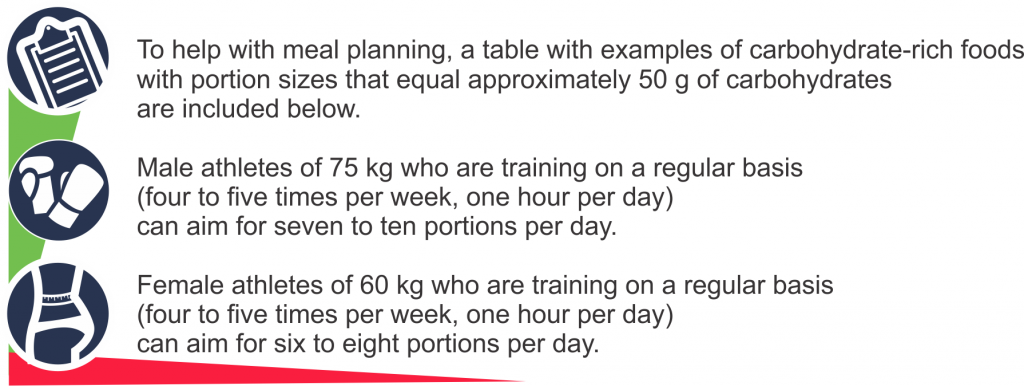

Athletes generally need more carbohydrates compared to the general population. However, factors such as total daily energy expenditure, type of sport, sex, age and weight of the athlete need to be considered in estimating specific carbohydrate needs. The amount of carbohydrates is usually estimated based on the amount of exercise (taking into consideration the duration, frequency and intensity of exercise) and the athlete’s body weight as follows:

• When should an athlete eat carbohydrates?

Try to eat five to six meals a day and include a carbohydrate food source with every meal. Athletes should also eat carbohydrates before and during hard or long exercise sessions to fuel the session, and thereafter to help with recovery.

Fat as fuel food

• Why should an athlete eat fat?

Fat provides more than double the amount of energy compared to carbohydrates, and the body’s fat stores are adequate to fuel many hours of exercise. However, since carbohydrates are more readily available and easier to use especially during higher intensity exercise, a high percentage of fuel comes from carbohydrates and only a small amount from fat. It is important to note that the body’s carbohydrate stores are small, so athletes competing in longer events (e.g. marathons and lengthy cycle races) will also use fat as fuel. Fat is not just a second fuel source, it is also important in an athlete’s diet as it provides fat-soluble vitamins and essential fatty acids, protects the internal organs, and keeps the body warm.

• Where can an athlete find good fats?

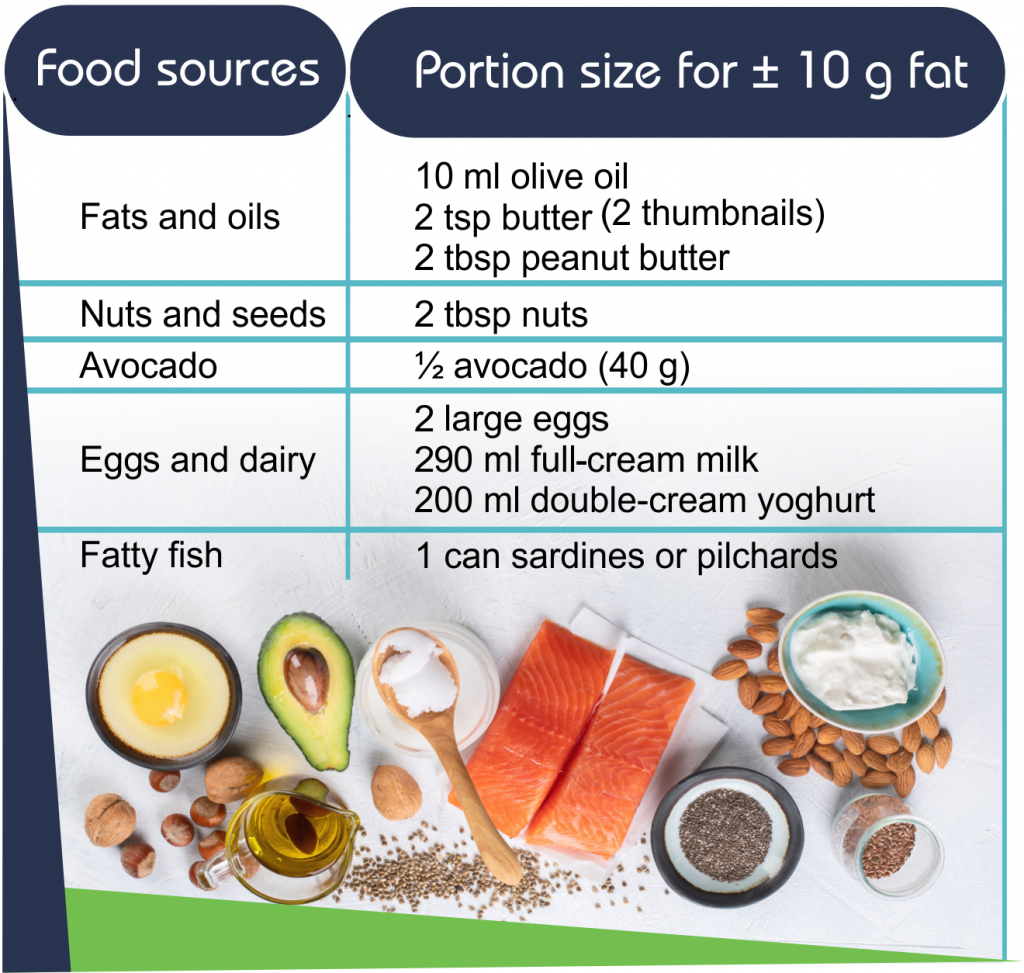

Not all fats are equal. Athletes need to include the healthy (unsaturated) fats in their diets and limit the unhealthy (saturated) fats. Good sources of fat are plant-based fat sources including avocado, nuts and seeds, olives/olive oil and peanut butter. Eggs, full-cream yoghurt/Greek yoghurt also contain fat and are good sources of protein. Fatty fish (e.g. salmon, tuna, and sardines) is another protein-rich source that is high in omega-3, the heart-healthy fat.

• How much fat does an athlete need?

Athletes do not necessarily need more fat compared to the general population. In fact, some athletes need to maintain a lean physique to perform well (e.g. runners and gymnasts) and should therefore carefully control the amount of fat they eat. The amount of fat is not only dependent on ideal body composition (associated with the type of sport), but also on total daily energy expenditure, the nature of the sport and the athlete’s sex. The recommended fat intake for athletes is from 20% to 35% of total daily energy intake. For an athlete weighing 70 kg, this amounts to approximately 80 g of fat per day.

The table below contains examples of good sources of fat with portion sizes that equal approximately 10 g of fat. Male athletes can choose seven to eleven servings per day, while female athletes should aim for five to eight servings per day.15

• When should an athlete eat fat?

Fats/fat food sources are often combined with main meals (e.g. fish for supper), eaten in combination with other foods (e.g. butter on bread, olives in salads) or used in meal preparation (oil for frying/roasting). Athletes can also eat full-cream yoghurt, nuts and seeds, or boiled eggs as a snack in-between meals. However, fat or foods high in fat should not be eaten before or during exercise. Too much fatty or fried food on the day of a competition might lead to sluggishness. Fat decreases the transit time of food through the gut, which means that in the presence of a lot of fat, carbohydrates would not be readily available. Therefore, limit the use of fatty or fried foods on competition days.13,14

4.3  Building foods

Building foods

• Protein facts

- Protein comes from the Greek word proteios, meaning ‘of prime importance’.

- Protein contains nitrogen – something not found in carbohydrates or fats – which makes protein unique.

- Amino acids are the building blocks of protein. Some amino acids are called ‘essential’, which means that you can get them only from food. ‘Non-essential’ amino acids, though, can be manufactured by your body and therefore they do not have to come from food sources.

- Food from animals (meat, poultry, fish, milk and eggs) contains all the essential amino acids your body needs and is therefore called ‘complete protein’. Protein from plant sources (e.g., baked beans, seeds, legumes and grains) often lacks one or more essential amino acids and is therefore called ‘incomplete protein’.

- Proteins have two main roles: some help to drive chemical reactions in the body (functional proteins) and others give tissue and organs their shape, strength and flexibility (structural proteins).13

• Why should an athlete eat building foods (protein)?

Protein is involved in the development, growth, and repair of muscles and other bodily tissue and is therefore critical for recovery from physical activity.

Protein can also be used as a fuel; however, it is not used efficiently and therefore is not a fuel food preferred by the body. It can, however, boost glycogen storage, reduce muscle soreness and promote muscle repair. Those who are active regularly may benefit from consuming a portion of protein at each meal and spreading out protein intake throughout the day.13

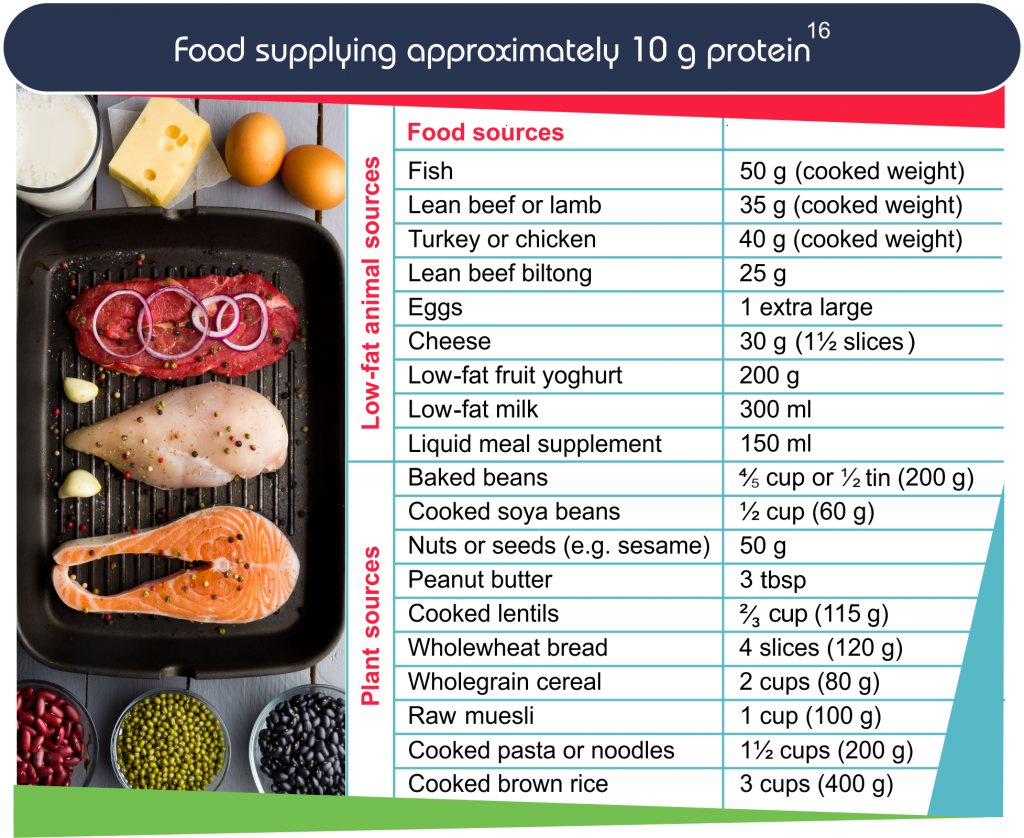

• Where can an athlete find protein?

Protein is found in a variety of foods, including grains and vegetables, but is mainly concentrated in milk, meat and beans (soya products, nuts, seeds, beans, and other non-animal products).13

• Considerations when planning protein intake

Athletes participating in regular sport and exercise may need a higher protein intake to promote tissue growth and repair. However, it is not just the amount of protein that counts, but also when it is consumed. Protein should be consumed in the right amounts, at the right times, and when in a reasonably good energy-balanced state. Randomly eating more protein does not accomplish what the body needs.15

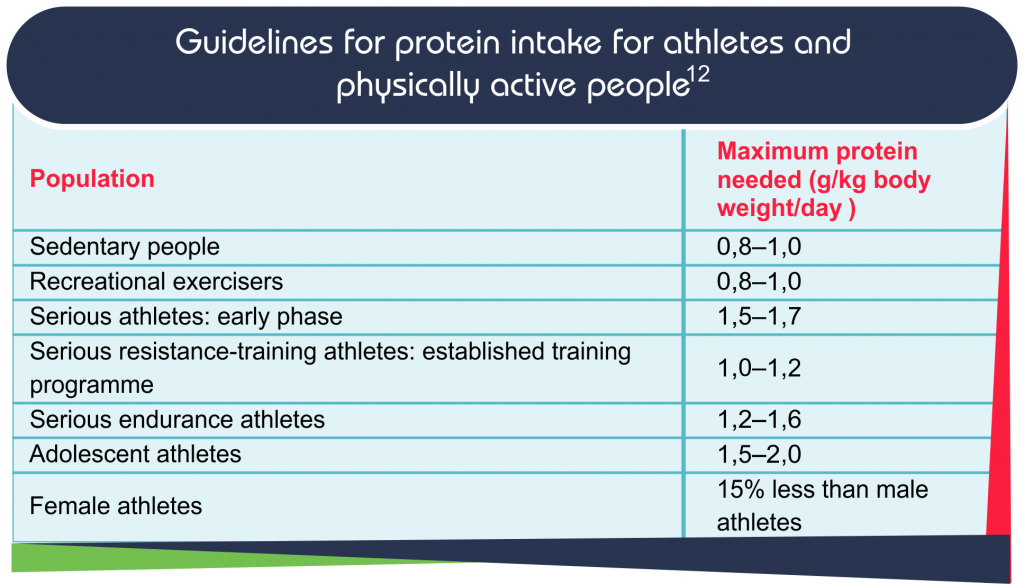

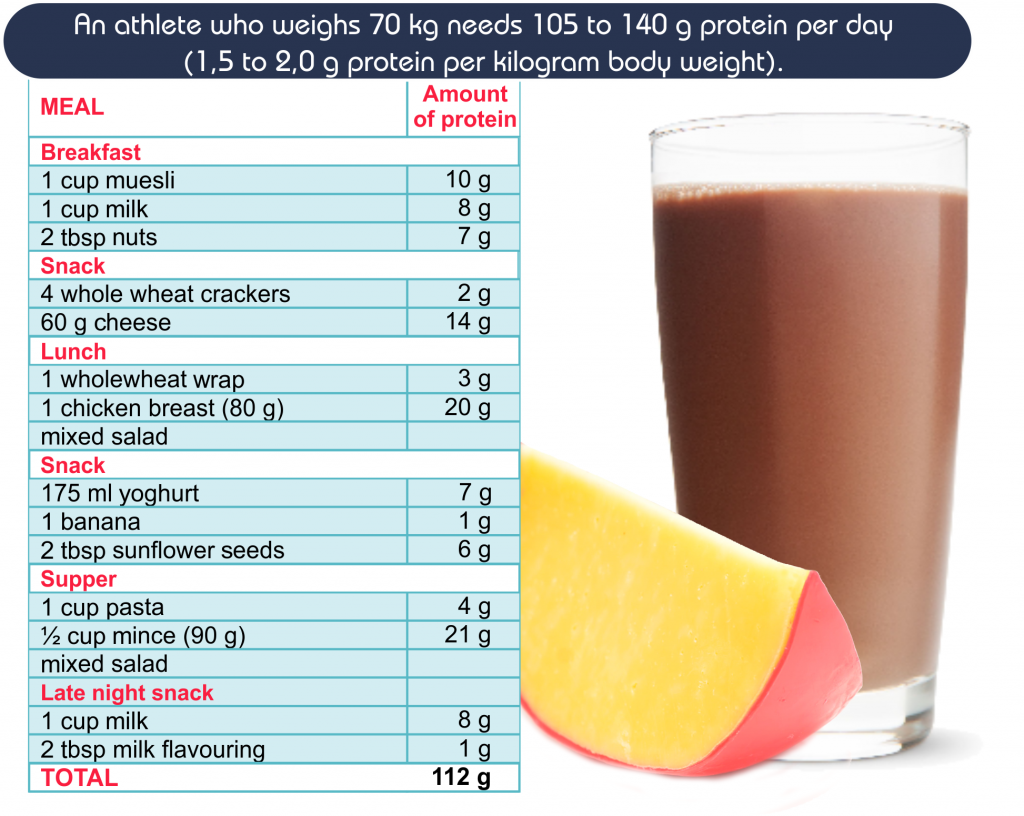

• How much protein does an athlete need for sports training?

The protein recommendation for athletes is an intake of ± 1,2 to 2,0 g protein per kilogram bodyweight per day. Recent recommendations to stimulate muscle protein synthesis maximally suggest an optimal protein intake of 20 to 25 g (or the equivalent of ± 0,25 g/kg) per meal.12

• When should I eat building foods (protein)?

It is recommended that athletes eat a building food (protein) every three to five hours throughout the day and specifically between 30 minutes and two hours after training. It is beneficial to take the building food with a fuel food (carbohydrate source).17

What does it look like on a plate of food?

4.4  Protective food

Protective food

• Why should an athlete eat protective foods?

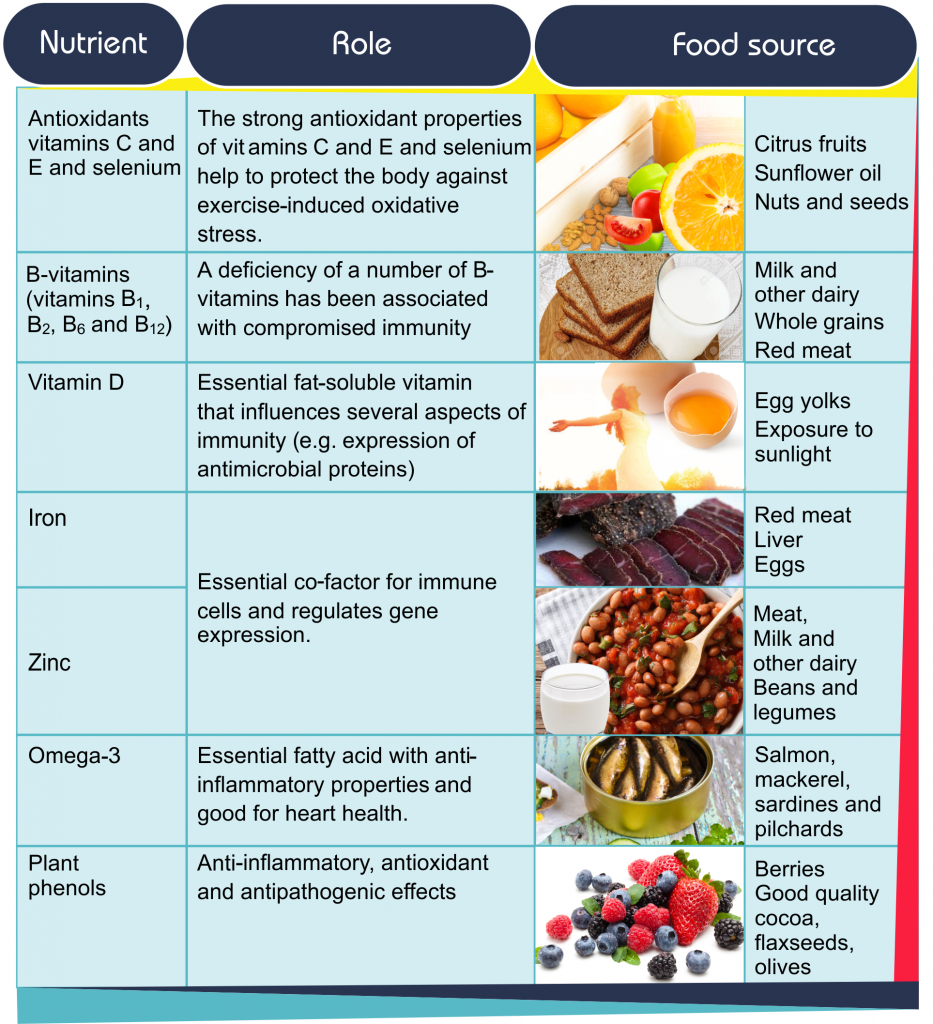

Carbohydrates, fat and protein (fuel foods and building foods) help athletes train and compete, and repair muscle and other bodily tissue. But athletes also need to stay healthy and maintain their immune systems. Intense and continuous training causes oxidative stress, and combined with life’s other stressors (work, environment, not enough sleep, travel, and relationships) puts strain on an athlete’s immune system. A sick athlete cannot train or compete so it is important that athletes take care of their health. Although enough energy and macronutrients are also important for health, protective foods contain vitamins and minerals and other important nutrients that are especially important for the immune system (e.g. antioxidants [Vitamins C, E, and selenium], B-vitamins, Vitamin D, iron, zinc, omega-3, and polyphenols).18,19

• What are good examples of protective food sources?

The most important source of vitamins and minerals are fruit and vegetables. Since different colours of fruits and vegetables contain different vitamins and minerals, athletes should eat a variety of colours. The table below provides more examples of food sources for the specific nutrients that are important for a healthy immune system.19-21

• How can athletes include enough protective foods in their diet?

Aim to eat at least five fruits and vegetables per day (including one to two green vegetables, one to two yellow vegetables and two to four different fruits). Include whole grains in your carbohydrate sources and ensure that you eat the recommended protein portions (including milk and animal proteins). If you are a vegan/vegetarian you will need to plan your food combinations carefully to ensure that you also meet your iron, zinc, and Vitamin B12 requirements.

• When should an athlete eat protective foods?

Protective food sources such as vegetables and protein sources are ideal to include in main meals (salad during lunch time; vegetables at supper time), while fruit and dried fruit are ideal snacks between meals.

General dietary tips to stay healthy

- Eat a variety of foods, including a variety of fruit, vegetables and grains to meet micronutrient requirements.

- Eat enough food to match energy expenditure and maintain energy availability.

- Eat enough carbohydrates and protein to meet minimum training requirements.

- Eat enough fat (not less than 15% to 20% of total energy intake) and focus on healthy fat sources with essential fatty acids (omega-3).

- Eat enough carbohydrates during longer training sessions (> 60–90 min) to keep your blood sugar levels stable.

5. From facts to plate

Meal planning will help to fit all the pieces into a beautiful puzzle that supports training and competition performance. Herewith a review of the basic principles:

Eat something within an hour of waking up. Eating breakfast on a consistent basis tends to result in a better nutritional profile and a lower risk of becoming overweight. It may also improve cognitive function.22

Keep the meal balanced: combine a fuel food (carbohydrate in starch) with a building food (protein) and a protective food (fruit or vegetable). Remember the intake of fluid with this meal.

Breakfast choices:

- Porridge (e.g. maize or oats) or wholegrain cereal with milk, plus yoghurt and a banana

- Wholewheat bread with poached eggs and freshly squeezed orange juice

- Wholewheat crackers with low-fat cottage cheese, honey and apple slices

Eat a snack or a meal every two to three hours for better blood glucose control. Keep snacks small and nutrient-rich. Remember to include a building food (protein) as part of the snack.15,23

Snack choices:

- Wholewheat crackers with cheese

- Drinking yoghurt

- Flavoured milk

- Wholewheat bread with peanut butter

- Fruit salad served with yoghurt

- Biltong and fresh fruit juice

- Almonds with raisins

Main meals (lunch and supper) should include a fuel food (carbohydrate source), a building food (low-fat protein choice) and a generous helping of protective food (vegetables or salad).

Main meal choices:

- Wholewheat pita bread with chicken strips and stir-fried vegetables

- Pasta with tuna and tomato-and-onion sauce

- Baked potatoes with a lean mince filling, served with a Greek salad

- Rice mixed with lentils and roast butternut

- Pasta salad with sliced eggs and tomatoes, served with freshly squeezed fruit juice

- A green salad with tomatoes, nuts and balsamic dressing, served with wholewheat bread

- Vegetable soup served with wholewheat rolls

- Brown rice with roast chicken breasts and mixed vegetables

- Baked sweet potato with roast pork chops and Greek salad

- Stiff maize meal porridge with tomato stew and beetroot salad

Drink fluids like water, milk, fruit juice or iced tea throughout the day.

Be sure to eat fuel food (carbohydrate-rich snack) before training.12,15

For training sessions that last longer than 60 to 90 minutes, drink a carbohydrate-based drink during the session.12,15

Eat a recovery snack as soon as possible after the training session. Be sure to include fuel foods (carbohydrate source), building foods (protein) and liquid.12,15

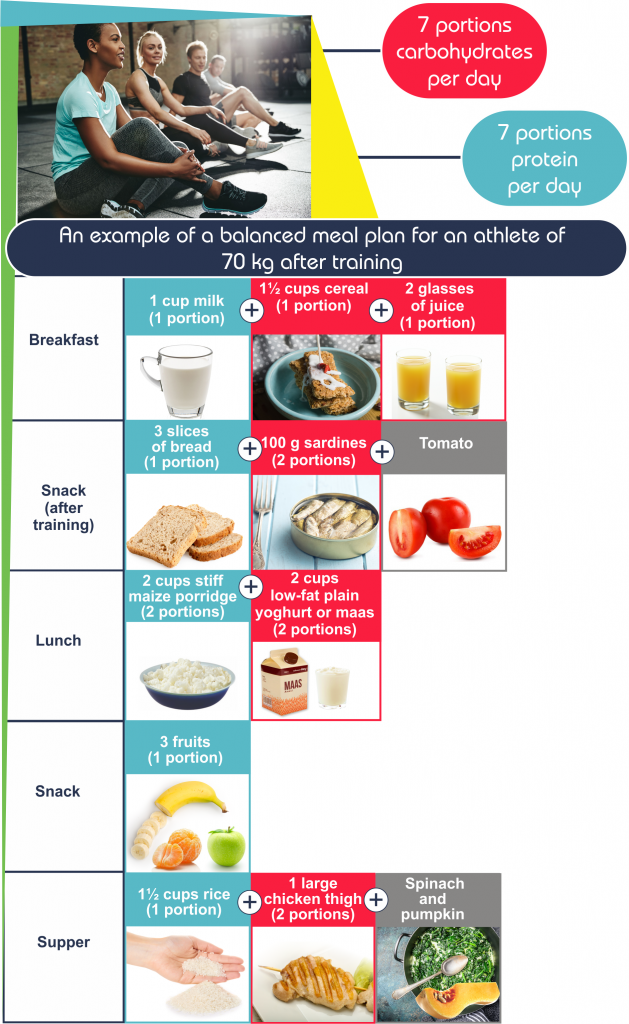

An example of a balanced meal plan for an athlete of 70 kg after training:

*Carbohydrate portions *Protein portions *Add some vegetables to help fight flu or other infections!

6. Hype about hydration

Water is essential to life and has many important roles in the body. It maintains blood volume and regulates body temperature, and during exercise the body cools itself by sweating. Sweating ultimately results in a loss of body water and potentially some electrolytes, which, if not replaced, can lead to dehydration and compromised performance. Therefore, athletes should make sure that they prevent dehydration by drinking enough fluid.

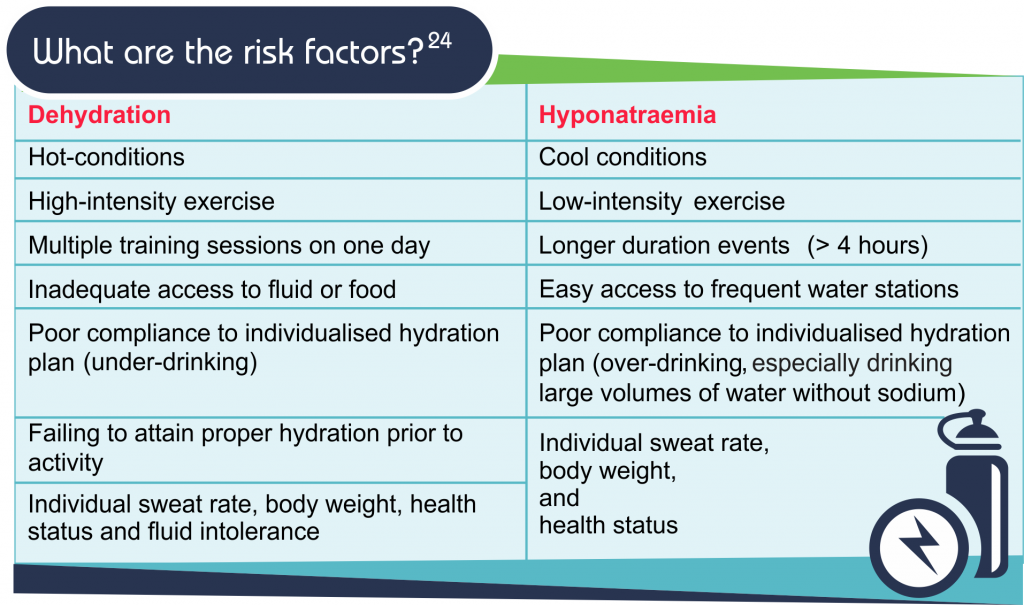

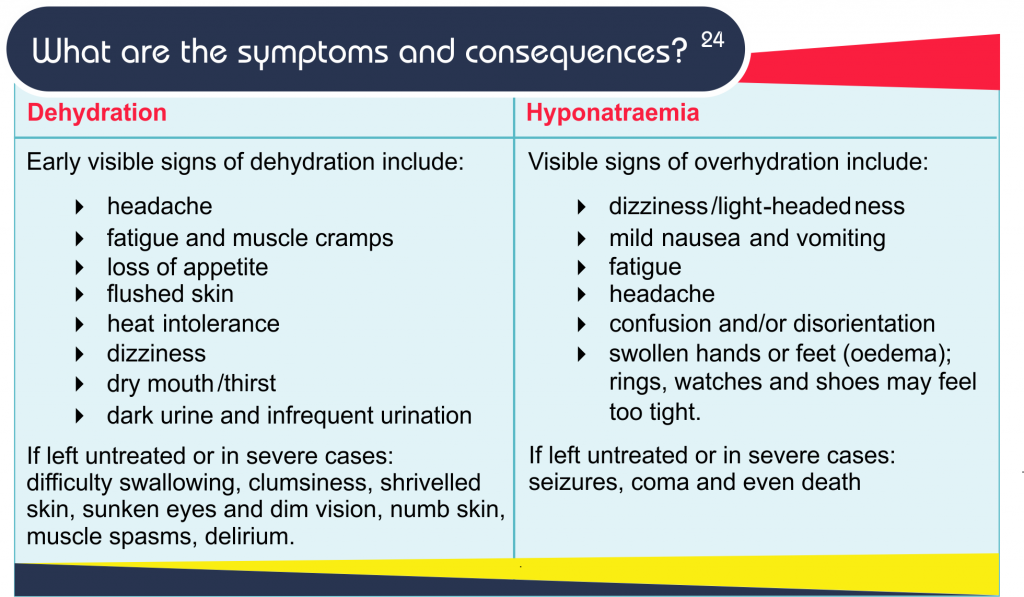

Sweat losses usually increase with an increase in exercise intensity, temperature and humidity. Athletes performing high-intensity exercise in hot weather should therefore pay special attention to replace fluid losses. In cool weather or when the exercise intensity is low, sweat loss may be small. Similar to not drinking enough fluid, drinking more than necessary can also interfere with performance and can be dangerous to health. Drinking too much fluid (or over-hydrating) during exercise can dilute the levels of sodium in the bloodstream resulting in hyponatraemia. Both dehydration and hyponatraemia should be prevented during exercise and athletes should aim to maintain an optimal hydration status.

Dehydration results in an increase in heart rate and body temperature. There is also an increased perception of how hard the exercise feels, especially when exercising in the heat, resulting in a reduction in physical and mental performance (including concentration and decision-making). Dehydration can also increase the risk of nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and other gastrointestinal problems during and after exercise.25,26

The past decade has seen controversy over guidelines for fluid intake during sport. Fluid requirements differ for different sports, but also for different individuals participating in the same event on the same day. What is clear is that fluid needs are highly individualised and there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to fluid intake. Fluid intake depends on fluid/sweat loss, so athletes should be able to monitor their own hydration status in order to adjust fluid intake accordingly.25,26

How to monitor hydration status

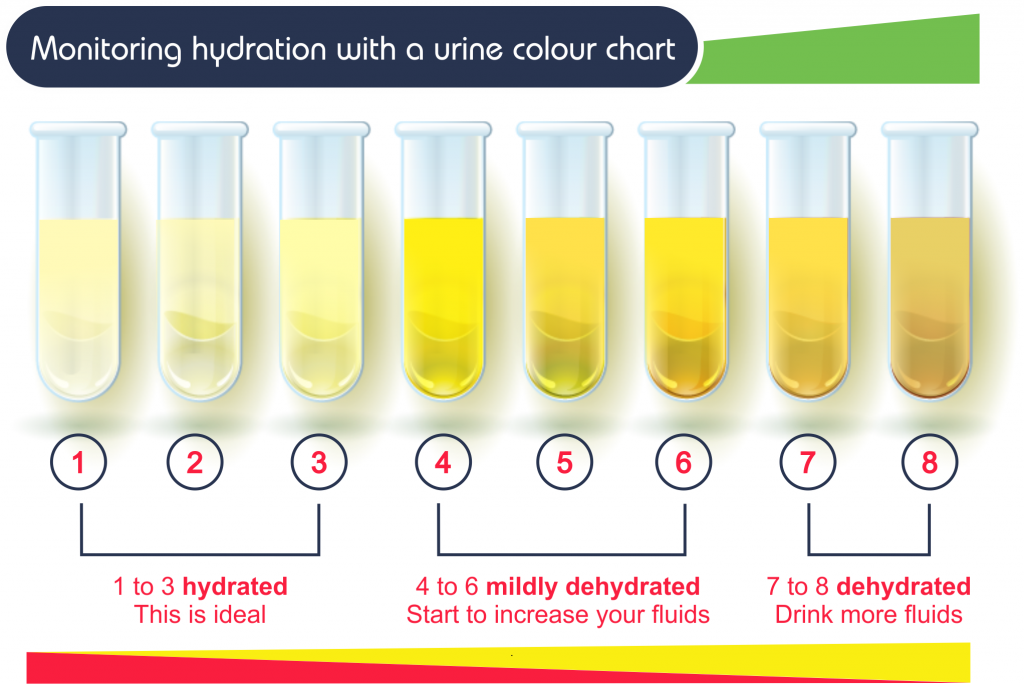

Athletes can start to monitor their day-to-day hydration status when waking up every morning. Three easy indicators to monitor include body weight, urine colour and thirst. A daily loss of more than 0,5 to 1,0 kg of body weight, a small volume of dark-coloured urine (like apple juice or darker), and the noticeable sensation of thirst are all symptoms of dehydration. When two or more of these symptoms are present, dehydration is likely. If all three markers are present, dehydration is very likely and greater attention should be given to 24-hour fluid intake.27

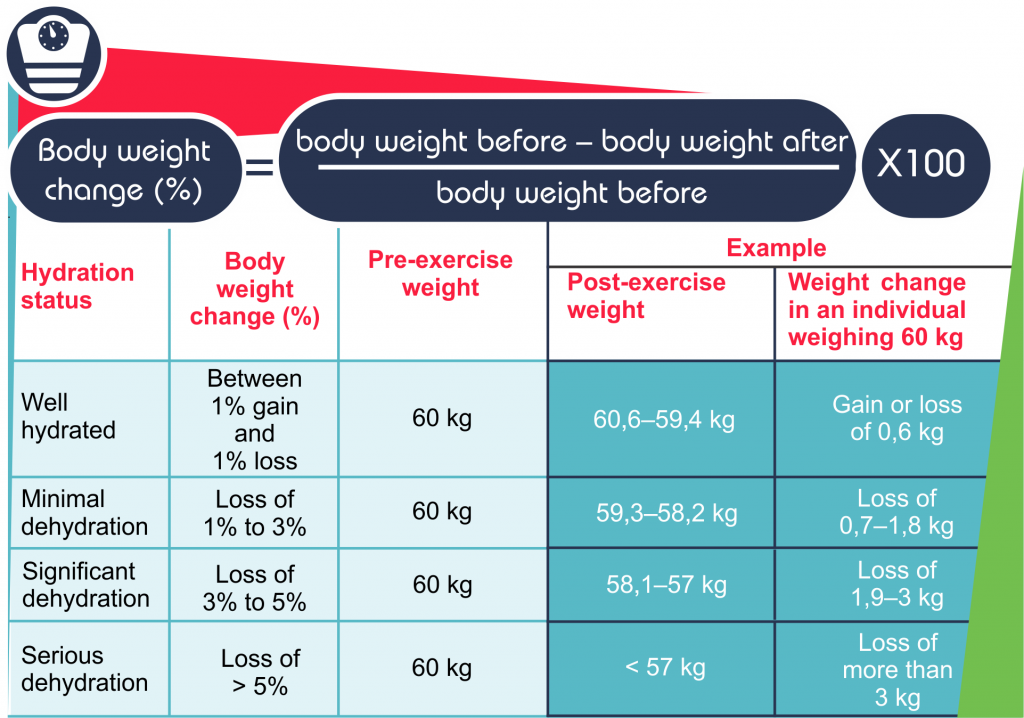

A change in body weight is also an indication of an athlete’s hydration status following exercise. The percentage change in body weight can be calculated as follows:

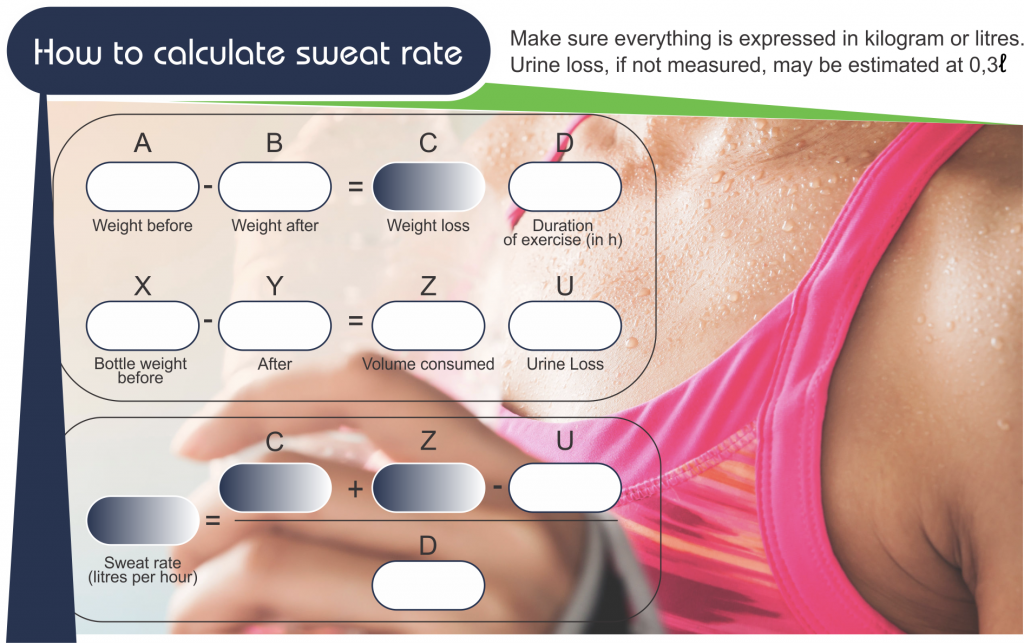

Drinking fluid during exercise is necessary to replace the fluid lost through sweat. The amount of fluid consumed should therefore reflect the amount of fluid lost through sweat. As sweat rates vary among individuals, knowing your unique sweat rate and how much fluid you should be drinking is important.

General consideration for achieving an optimal hydration status

- There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to achieve optimal hydration. Factors that can influence fluid requirements and individual hydration strategies include type of sport, exercise intensity, exercise duration, individual characteristics of the athlete (including sweat rate), weather conditions, and opportunities to consume fluid during the events.

- Athletes should drink enough before exercising, so that they can start the activity in a well-hydrated condition.

- Athletes should be sensitive to onset of thirst as the signal to drink, rather than ‘staying ahead of thirst’.

- Experiment with competition drinking strategies during training (e.g. using wearable drinking systems as a substitute for water stations).

- Team sport athletes should make the most of opportunities to drink fluids (during intervals or injury time).

- Adopt a pattern of drinking small amounts of fluid at regular intervals during exercise rather than trying to drink large volumes all at once. Start fluid replacement early and top up frequently as this will maintain gastric volume and increase fluid absorption.

- Active cooling should be part of the recovery plan. Avoid long, hot baths or prolonged sauna or spa sessions. If such activities are necessary, drink extra fluids.

- You will continue to lose fluids through sweating and urine losses after you finish exercising, so plan to replace 125% to 150% of the fluid that you’ve lost during the session over the four to six hours after you stop exercising.

- Drink fluids in conjunction with salty recovery snacks (e.g. potatoes sprinkled with salt, cereal, pretzels, milk) to help your body rehydrate more effectively.

What are the best fluids to drink?

There are many fluid options available, and it is important to determine what works best for you as individual. Plain water can be an effective drink for fluid replacement, especially in low intensity and short duration sport. If you prefer an alternative, consider consuming a diluted sports drink or diluted fruit juice (two cups of water, one cup of fruit juice). Sports drinks (6% to 8% carbohydrate solution) can be useful during some activities, especially high-intensity or endurance sport, as they contain both carbohydrates for fuel and flavour, and electrolytes (sodium) to help the body ‘hold on to’ fluid more effectively and stimulate thirst. During ultra-endurance events, athletes may prefer to consume water and food; not only to match fluid to required energy intake, but also to use the water to cleanse the mouth of flavours that can become unpleasant after prolonged consumption.12,26

Practical guidelines

- Monitor weight, urine colour, and thirst sensation to guide day-to-day adequacy of water and electrolyte consumption.

- Urine that is plentiful, odourless and pale in colour (like pale straw) generally indicates that a person is well hydrated.

- Dark, strong-smelling urine (like the colour of apple juice), in small amounts could be a sign of dehydration.

- Certain foods, medications and vitamin supplements may cause the colour of urine to change even though you are hydrated.

- Make sure that drinks are easily accessible. They should be in a container that allows for easy drinking with minimal interruption of exercise.

- Drinks should be cool (not cold) and palatable, and contain the optimal amount of carbohydrates applicable for the specific event (in particular high-intensity and endurance events). Sports drinks (6% to 8% carbohydrates) are good options since they empty faster from the stomach than soft drinks (which generally contain 10% carbohydrates), while also helping to replace sodium losses. Drinks with carbohydrate concentrations greater than 10% to 15% may cause gastric cramps.

7. Intake before exercise

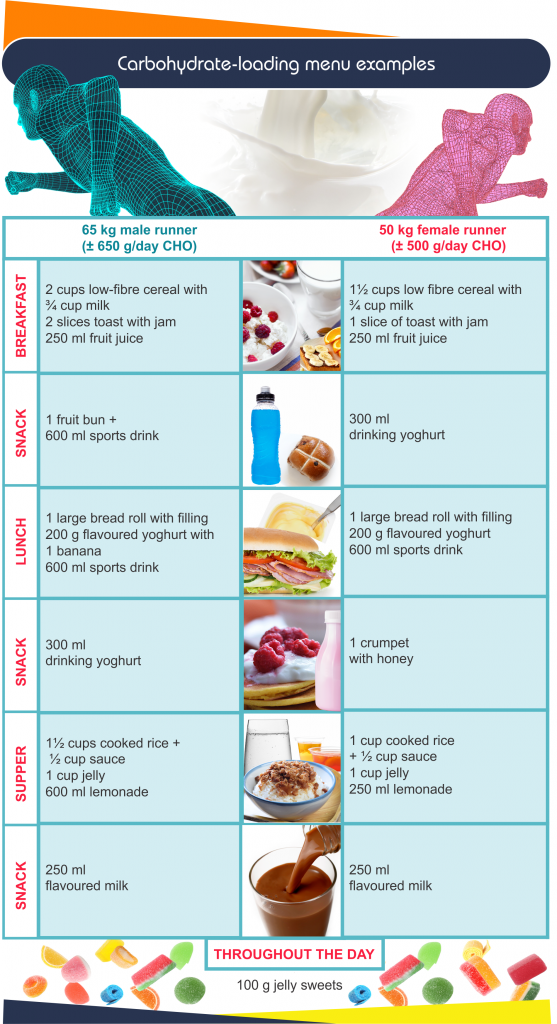

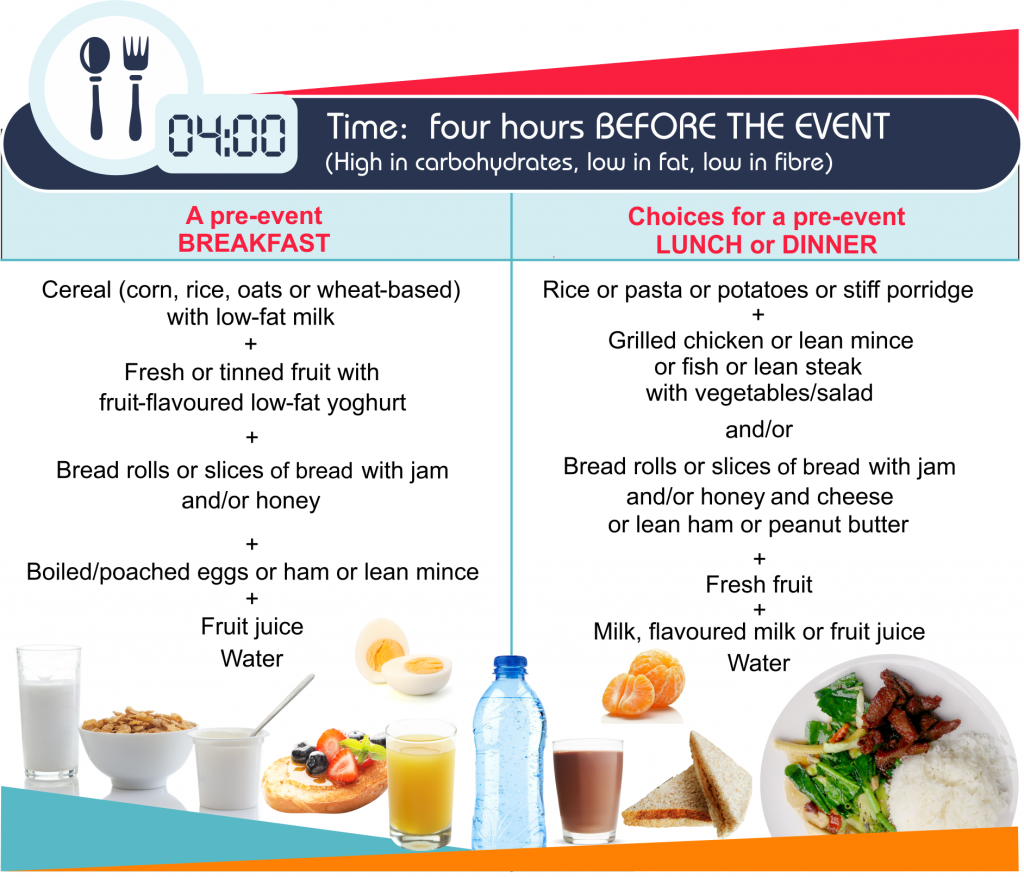

Exercise requires energy, and in the section on fuel foods we had a look at carbohydrates as main fuel source during exercise. In some instances, athletes may prefer to train with a low carbohydrate availability (e.g. train early in the morning without eating a pre-exercise snack or meal) to benefit from specific training adaptations (e.g. improved fat oxidation). The choice of pre-exercise carbohydrate intake does not only depend on the intensity and duration of the session, but also on what the athlete wants to achieve with the specific exercise session (e.g. a faster time or improved performance vs. the activation of acute cell-signalling pathways). In some instances, athletes may not only benefit from a pre-exercise meal in the hours before the event to replenish liver glycogen stores, they may also benefit from a high-carbohydrate diet in the days leading up to the event (i.e. carbohydrate loading) to maximise muscle glycogen stores.28

• ![]() When should an athlete consider carbohydrate loading?

When should an athlete consider carbohydrate loading?

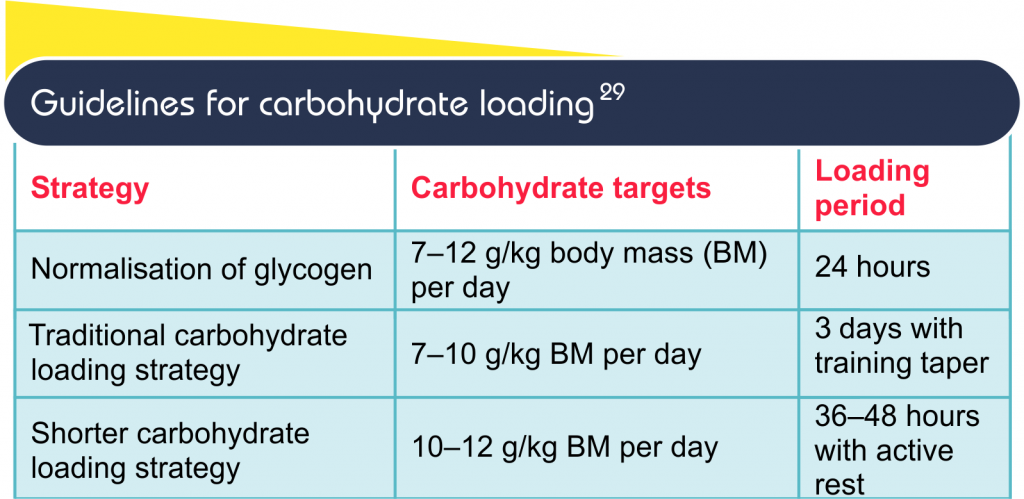

Athletes taking part in activities likely to involve continuous exercise for more than 90 minutes, or activities that involve repeated high-intensity exercise bursts can consider carbohydrate loading. By maximising muscle glycogen stores, carbohydrate loading can help to postpone fatigue and maintain a higher work pace during exercise. However, athletes should experiment with carbohydrate loading before training sessions of longer duration since it results in slight weight gain (additional water is stored with glycogen). Athletes may also experience gastrointestinal discomfort during the loading phase if they are not used to eating a high volume of carbohydrate-rich foods (like refined carbohydrates).

It is important to note that even if athletes are carbohydrate-loaded, they still need to eat additional carbohydrates during endurance and particularly ultra-endurance events to maintain normal blood glucose levels. Carbohydrate loading also does not increase performance when high carbohydrate availability is maintained with a pre-exercise carbohydrate meal and adequate carbohydrate ingestion during exercise. Athletes who experience discomfort with carbohydrate loading can therefore aim to normalise their muscle glycogen stores by including regular carbohydrate meals and snacks (as per their normal training diet) the day before. Inclusion of a pre-exercise meal and enough carbohydrates during the event is then very important (intake during exercise will be discussed in the next section).

General guidelines for carbohydrate loading

|

• When should an athlete consider a pre-exercise meal?

Athletes taking part in endurance events or training sessions of longer duration (> 90 minutes) with the aim to perform, as well as athletes taking part in shorter high-quality training sessions or matches (where it is important to maintain a certain exercise intensity) should eat a pre-exercise meal to ensure that they start the event with enough fuel. The aim of a pre-exercise is not only to fuel muscle and liver glycogen stores, but also to ensure that the athlete is well-hydrated. A pre-exercise meal can also prevent hunger and avoid gastrointestinal discomfort during the event and have psychological benefits.12

Sources of carbohydrates:

- Good carbohydrate choices include low-fat and low-fibre carbohydrates such as cereal, porridge, bread, potatoes, pasta, crumpets and scones. Carbohydrate sources from food and fluids are effective in topping up glycogen stores.

- The choice of carbohydrate source is based on athlete preference (e.g. taste), practicality and availability (e.g. pre-match travel, stadium/event offerings).

Amount of carbohydrates:

- 1 to 4 g carbohydrates/kg body mass.

Timing of pre-exercise meal:

- One to four hours before the event. A bigger meal (200 to 300 g of carbohydrates) can be consumed three to four hours before the event, followed by a smaller meal/snack (50 to 150 g carbohydrates) one to two hours before the event.

Co-ingestion of other nutrients:

- Fat, fibre and protein can be included in low to moderate amounts according to risk of gut issues, especially one to two hours before an event. Since hydration is important, fluid should also be consumed before exercise. Drink 500 ml water two hours before the event and another 300 to 500 ml of water 15 to 30 minutes before the start. A carbohydrate-rich drink can also be considered to combine fluid and carbohydrate needs.

General guidelines for pre-event meals

|

NOTE: For any individual differences or needs required for a specific sport, it is recommended to contact a professional dietitian to assist you with your personal meal plan.

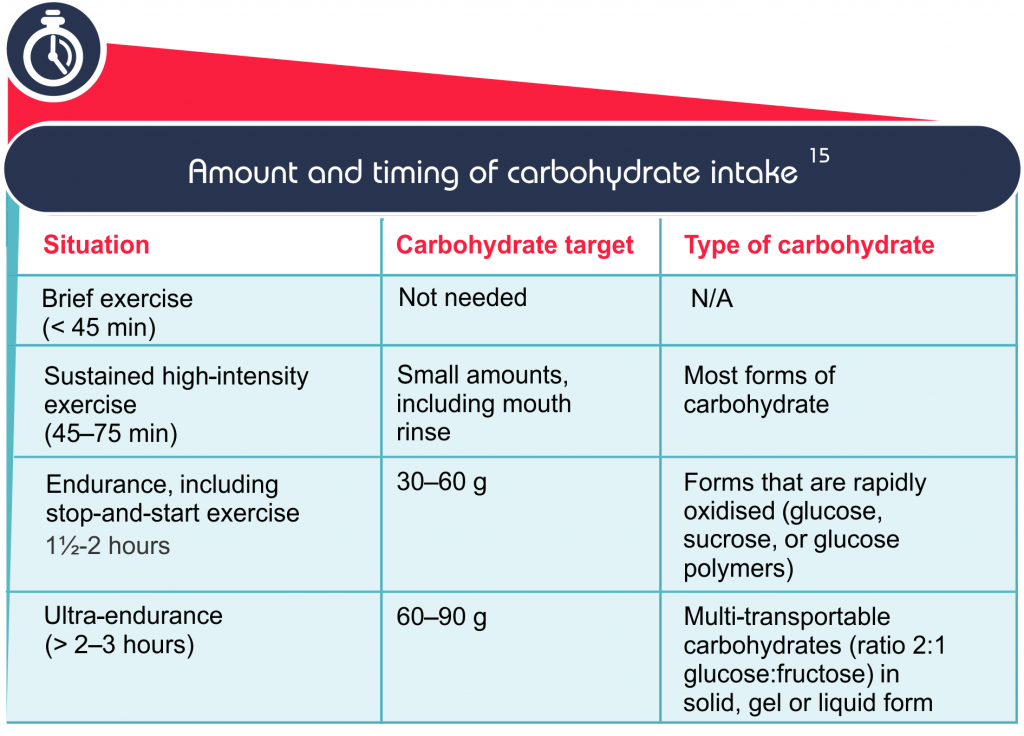

8. Intake during exercise

The main considerations from a nutritional point of view are to maintain energy levels and hydration levels (refer to hydration section for details on hydration). The body’s carbohydrate stores (liver and muscle glycogen) provide an important but fairly limited supply of energy during exercise. Athletes may choose to train with a low carbohydrate availability and not only skip the pre-exercise meal, but also refrain from consuming carbohydrates and fluid during exercise to benefit from specific training adaptations. The choice of consuming carbohydrates during exercise mainly depends on the intensity and duration of the session, but the specific training adaptation that an athlete wants to achieve with the training session must also be considered (e.g. a faster time/improved performance vs. the activation of acute cell-signalling pathways).28

• ![]() What is the value of taking carbohydrates during exercise?

What is the value of taking carbohydrates during exercise?

During very high intensity exercise, the athlete predominantly uses carbohydrates as fuel. The liver glycogen stores that are responsible for maintaining normal blood sugar levels during exercise can be depleted within one to two hours of moderate to high-intensity exercise. Adequate carbohydrate intake during exercise can prevent hypoglycaemia and muscle breakdown when carbohydrate stores in the form of glycogen become depleted. Carbohydrate intake during exercise is also the best proven strategy to enhance performance since it spares endogenous glycogen levels and helps athletes to sustain a higher exercise intensity. Even athletes who just rinse their mouths with a carbohydrate drink during exercise can benefit from the positive effects of ‘mouth sensing’ on the central nervous system.

• When should an athlete take carbohydrates during exercise?

Athletes taking part in endurance events or training sessions of longer duration (> 60 to 90 minutes), or in shorter events (45 to 75 minutes) with repeated intermittent high-intensity bouts (e.g. team sport including soccer, hockey, or rugby) should consider consuming carbohydrates during exercise. Sufficient carbohydrate intake during exercise is even more important when athletes start the event with low liver and muscle glycogen levels (i.e. if they did not eat a pre-exercise meal or normalised/maximised their muscle glycogen levels). Endurance and ultra-endurance athletes who aim to enhance their ability to consume and use more carbohydrates during events should train with a high carbohydrate availability and consume sufficient amounts of carbohydrates during training to train the gut.30

• Sources of carbohydrates:

- High glycaemic index carbohydrate choices that are readily available such as energy drinks, jelly sweets and energy gels.

- Carbohydrate sources from solid foods, gels and liquids are effective in maintaining blood glucose levels.

- The choice of carbohydrate source is based on preference (e.g. taste), tolerance, practicality, and availability (e.g. provided by race organiser/event offerings).12

General guidelines for carbohydrate intake during exercise

|

To reduce the risk for gastrointestinal symptoms during exercise31

|

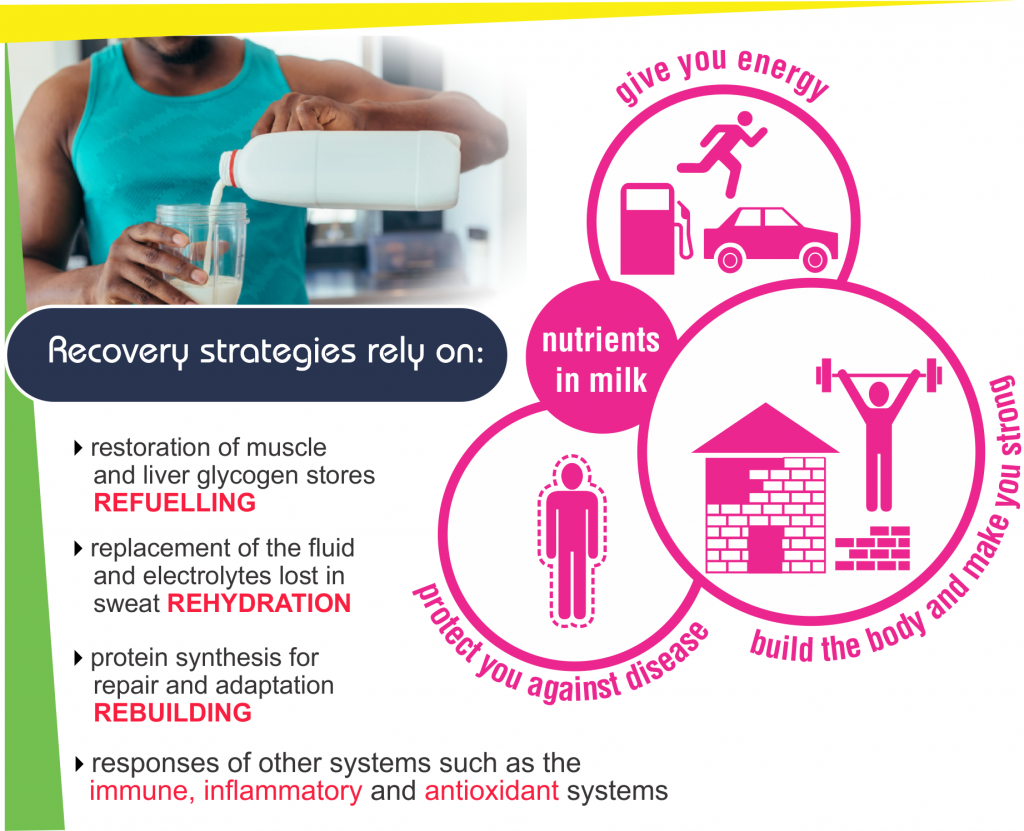

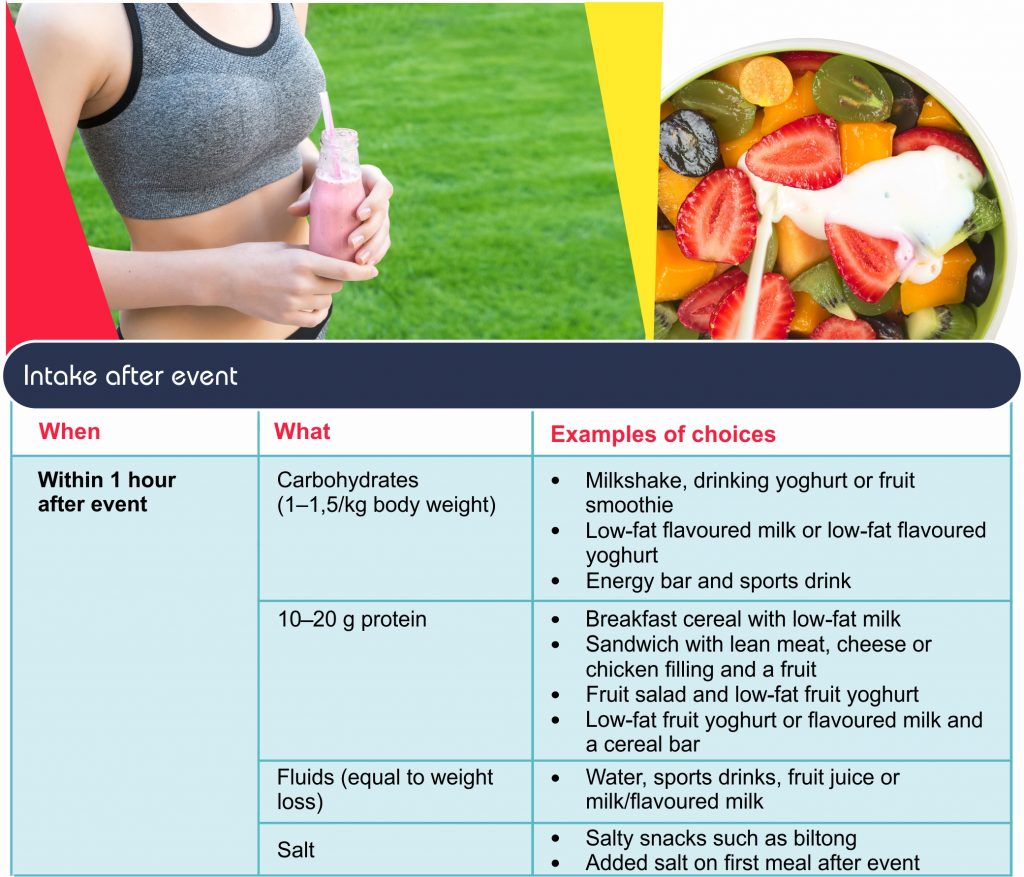

9. Intake after exercise

An increase in training load is associated with an increase in fitness level, but what is often overlooked is that real gains in exercise capacity occur when the body is at rest and able to recover. Recovery aims to maintain the athlete’s physical and mental readiness to perform. Recovery nutrition promotes muscle regeneration, glycogen restoration, reduces fatigue and supports physical and immune health, helping the athlete to prepare for the next competition or training session. Each training session is different regarding sweat rates, muscle fuel depletion, protein synthesis stimulation and damage or disruption incurred.12,32,33

• Restoration of muscle and liver glycogen stores (refuelling)

Carbohydrate intake after a training session aims to restore depleted muscle and liver glycogen stores.

Refuelling is highly dependent on the extent of glycogen depletion (glycogen that was used) and the type, duration and intensity of the exercise.

• ![]() Sources of carbohydrates:

Sources of carbohydrates:

- Carbohydrate sources from food and fluids are effective in restoring glycogen stores.

- The choice of carbohydrate source is based on athlete preference (e.g. taste), practicality (e.g. two sessions a day), and availability (e.g. post-match travel, stadium/event offerings).

- Carbohydrate choices of moderate to high glycaemic index can be advantageous because glycogen storage will, in part, be regulated by rapid glucose supply and insulin response.

- Sucrose may be preferential over glucose, owing to enhanced liver glycogen replenishment.

- Sports drinks, energy bars, whole grains, potatoes, sweet potatoes, rice, fruits and dairy can aid in recovery.

Carbohydrate dosage:

- 1,0 to 1,2 g carbohydrates/kg body mass

Timing of carbohydrate intake:

- Within the first hour after exercise and at 30-minute intervals for up to six hours after exercise for adequate glycogen resynthesis.

Co-ingestion of other nutrients:

- Where the intake of carbohydrates is sub-optimal, the addition of protein (0,3 to 4 g/kg/h) may help maximise glycogen resynthesis.

Guidelines to maximise refuelling

- Start consuming fuel foods (carbohydrates) soon after the session finishes. Aim for a recovery meal or snack providing ± 1 g carbohydrates per kilogram body weight, e.g. ± 50 g for a 50-kg female or 80 g for an 80-kg male)

- Continue with more snacks, drinks or meals to achieve a carbohydrate target of 1 g carbohydrates per kilogram body weight per hour for the first four hours of recovery, then resume the normal eating pattern.

- Carbohydrate-rich food choices include the following:

- breads (rolls, wraps, bagels, muffins)

- cereals (porridge, packaged cereals, muesli)

- grains (rice, pasta, noodles, couscous)

- sweetened dairy (flavoured milk, flavoured yoghurt, custard, maas)

- fruits, starchy vegetables (potatoes, sweet potatoes), and legumes (baked beans, kidney beans, chickpeas, lentils)

Mix-and-match meal examples:

- cereal with fruit

- baked beans on toast

- sandwiches or wraps

- fruit smoothies (blended fruit, milk, and yoghurt)

- meals served with grains (curry and rice, pasta and sauce, stir fry with noodles)

- desserts (pudding with custard, fruit with yoghurt, crumbed digestive biscuits with yoghurt)

When exercise intensity is low to moderate, exercise duration is short (< 90 min), and when there is ample time before the next exercise occasion (>8 h) less emphasis is placed on optimising carbohydrate guidelines for recovery in team sport athletes. In such scenarios, regularly spaced and nutrient-dense meals are likely to be sufficient to meet the recovery demands of the athlete.

❷ Protein synthesis for repair and adaptation (rebuilding)

Protein in the recovery meal facilitates muscle repair, muscle remodelling and immune function. Multiple factors modulate the response of muscle protein synthesis to protein intake, namely:

Sources of protein:

- Intact protein sources, as found in milk, accelerate recovery from muscle-damaging exercise.

- Leucine-rich sources such as whey protein and milk have been shown to be more effective to stimulate muscle protein synthesis compared to lower leucine-containing sources.

- Complete protein sources such as lean meats, poultry, fish, eggs, milk, yoghurt, soya, and tofu will aid recovery.

Protein dosage:

- Consume 0,3 g/kg (20 to 25 g) protein as soon as possible post-training, followed by 0,3 g/kg/meal across four to five meals per day.

Timing of protein dosage:

- The optimal protein dose should be distributed evenly (e.g. four to five times) throughout the day.

Guidelines to maximise rebuilding

- Consume a high-quality protein-rich food providing ± 20 to 25 g of protein soon after the exercise session has finished.

- Plan a pattern of snacks and meals to suit energy and lifestyle needs, incorporating 20 to 25 g protein every three to five hours.

- Include a protein-rich snack or meal before bed to support protein synthesis throughout the night.

- High-quality protein sources that provide ± 10 g protein include the following:

- two small eggs

- 25 g skimmed milk powder

- 300 ml milk

- 30 g (1½ slices) cheese

- 70 g cottage cheese

- 200 g tub of yoghurt

- 250 ml custard

- 35 g beef, lamb or pork (cooked weight)

- 40 g chicken (cooked weight)

- 50 g grilled or canned fish

- 120 g tofu or soya

- 400 ml soya milk

Rapidly digested protein sources (high in whey) that are particularly suitable for a post-exercise protein boost include the following:

- milk, flavoured milk, milkshakes, dairy/fruit smoothies

- yoghurt, drinking yoghurt, custard

• Replacement of the fluid and electrolytes lost in sweat (rehydration)

Rehydration is an important part of the recovery process, particularly when athletes need to participate in a subsequent exercise session within a short period (e.g. two sessions per day or when playing tournament matches).

Sources of fluids:

- The composition of a beverage consumed after exercise can have a significant impact on the rehydration process.

- The presence of sodium (± 20 to 50 mmol/ℓ) enhances palatability, stimulates physiological thirst, and affects fluid retention.

- Added carbohydrates also enhance fluid retention.

- Beverage composition is therefore an important consideration for post-exercise rehydration. The components found to have a significant positive impact are sodium, carbohydrates, and milk protein.

- Providing a chilled beverage with flavour and sweetness improves palatability and voluntary fluid intake after exercise.

Fluid dosage:

- To achieve rapid and complete rehydration, experts recommend 1,0 to 1,5 ℓ of a sodium-containing fluid for each kilogram of body mass lost.

Guidelines to maximise rehydration12,34

- Have a supply of fluids on hand that is palatable, suited to the conditions and suited to other recovery needs.

- When the fluid deficit is moderate to large (e.g. > 2 ℓ) and the rehydration period is 6 to 8 hours, have a planned fluid intake based on the deficit that needs to be replaced.

- It may require ± 125% of the estimated deficit to allow for ongoing fluid losses.

- Start consuming fluids soon after the session finishes and aim at consuming the target volume over the next two to four hours.

- Spread fluids over two to four hours rather than drinking large volumes at once.

- Fluid intake should be accompanied by electrolyte intake, e.g. drinking sports drinks that combine electrolytes (mainly salt) and liquid, or combining salty foods or snacks with fluid intake.

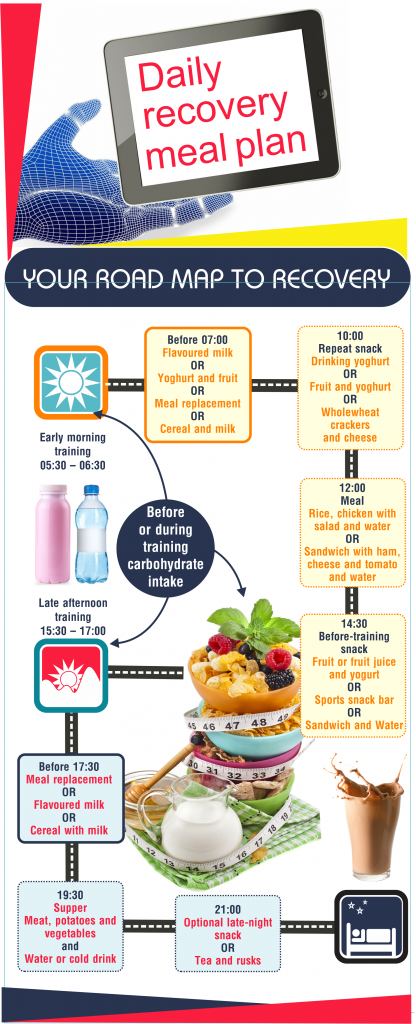

YOUR ROAD MAP TO RECOVERY

REMEMBER

If training only in the afternoon, the morning snack (before or during training) will fall away. When training only in the morning, move the afternoon snack a bit later, e.g. to 16:00. Take note that the snacks during training and recovery will then fall away but you will still have your normal supper and a late-night snack.

Examples of food combinations for recovery meals

The following combinations provide ± 60 g carbohydrates and ± 10 g protein:

- 300 ml milkshake or fruit smoothie

- 500 ml flavoured milk or drinking yoghurt

- 500 ml low-fat milk + two bananas

- 1 sandwich or roll with lean meat, cheese or chicken filling and a piece of fruit

- 1 cup fruit salad + tub (200 g) of low-fat yoghurt

- 700 ml sports drink + energy bar

10. Frequently asked questions and answers for athletes

10.1 How can a balanced diet enhance an athlete’s performance?

Numerous factors contribute to success in sport, and diet is a key component. An athlete’s dietary requirements depend on several aspects like the sport, the athlete’s goals, the environment, and practical issues. Specific dietary advice suited to the individual is increasingly being recognised, including day-to-day advice and specific advice before, during, and after training and/or competition. Recent research into energy availability shows the negative physiological and performance effects when training with low energy availability. Therefore, it is crucial that athletes make sure they get adequate energy intake to support training loads for optimal health and functioning.11 Optimal carbohydrate availability is a key strategy for many athletes. Recent research investigated the concept of periodised training with the emphasis on ‘eat for what you are going to need’. This places dietary strategies at the core of training session outcome goals.12,13

Carbohydrate intake during exercise maintains high levels of carbohydrate oxidation, prevents low blood sugar (hypoglycaemia), and has a positive effect on the central nervous system. Recent research has focused on athletes training with low carbohydrate availability to enhance metabolic adaptations, but whether this leads to an improvement in performance is unclear.

The benefits of protein intake throughout the day following exercise are well recognised. Athletes should aim to maintain adequate levels of hydration, and they should minimise fluid losses during exercise to no more than 2% of their body weight.12

A balanced diet consisting of the following components will enhance sport performance:

• Carbohydrates give energy

During times of high-intensity training an athlete needs adequate energy intake to maintain body weight, maximise training effects, and maintain good overall health. Carbohydrates are the main fuel source for athletes, who need larger amounts than the general population. However, factors like total daily energy use, type of sport, sex and age of the athlete, and environmental conditions need to be considered to estimate carbohydrate needs. Carbohydrate intake before and during exercise delays fatigue. It enables athletes to train for longer and increases carbohydrate oxidation to help maintain a higher intensity or to maintain their pace. Rinsing the mouth with carbohydrates during training can also lessen the perception of fatigue. It can therefore be used to minimise gastrointestinal symptoms due to carbohydrate ingestion.

• Protein helps muscle to recover

Protein requirements are higher for very active people. Protein intake will help muscle to recover from damage brought on during training, and enhance muscle protein synthesis.13,14 Proteins should be consumed in the right amounts, at the right times and when in a reasonably good energy-balanced state. Randomly eating more protein does not meet the body’s needs.15 The requirement can be met through diet alone, without using protein supplements.13,14

• Some fat is beneficial

Fat is important in an athlete’s diet as it provides energy, fat-soluble vitamins and essential fatty acids. It should make up no less than 20% to 30% of an athlete’s total daily dietary intake. For an athlete weighing 70 kg, this amounts to ± 80 g of fat a day. Too much fatty or fried food on a competition day might lead to sluggishness. Fat decreases the transit time of food through the gut, which means that in the presence of a lot of fat, carbohydrates are not readily available. Therefore, limit the use of fatty or fried foods on competition days.13,14

• Fluids help the body stay cool

Dehydration decreases exercise performance. It is important for athletes to consume adequate fluids before, during and after exercise to maintain optimal hydration.13,14

10.2 How can dairy products aid muscle recovery after sport?

Post-exercise recovery is a multifaceted process that will vary depending on the type and duration of the exercise, the time between exercise sessions, and the goals of the exerciser. The main nutrition considerations are:

- optimisation of muscle protein turnover;

- glycogen resynthesis;

- rehydration;

- management of muscle soreness; and

- appropriate management of energy balance.

Research has shown that drinking milk after exercise can be beneficial for acute recovery and chronic training adaptation. Milk enhances muscle protein synthesis after exercise and decreases post-exercise muscle soreness.35

Skeletal muscle is important for athletes due to its important role in movement, strength and metabolic regulation. Optimising skeletal muscle mass is important for health and performance. Exercise stimulates muscle building, but the process needs appropriate protein intake to optimise muscle protein synthesis. The source, amount and pattern of protein intake after exercise influence this synthesis. An intake of 20 g of a high-quality protein can be enough to maximise muscle protein synthesis after exercise. A litre of milk contains ± 36 g protein, which means that ± 600 ml should be adequate to maximise muscle protein synthesis. The high essential amino acid and leucine content of milk helps to maximise muscle protein synthesis and can reduce muscle soreness after some forms of exercise.35

10.3 What if an athlete needs to lose weight while training? (and a few words on intermittent fasting)

Many athletes aim to lose weight for aesthetic reasons (i.e. gymnasts), to ‘make weight’ for competition (i.e. combat sports) or to optimise their ratio of strength, power, or endurance to body weight for performance advantage. Optimal training requires energy, while weight loss often requires a restriction of energy intake. How can athletes maintain their energy levels during training, especially during endurance training, and at the same time create a big enough energy deficit to lose weight? More importantly, how can athletes lose unwanted fat mass, without losing muscle mass (referred to as high-quality weight loss). There are a number of major dietary strategies to optimise weight loss and performance in athletes, ranging from low-fat to low-carbohydrate/ketogenic diets. Intermittent fasting (IF) is also one of these major dietary strategies and has recently received a great deal of attention.36

| A few words on intermittent fasting37,38

Intermittent fasting (IF), also known as intermittent energy restriction, is an umbrella term for various meal-timing methods. The emphasis of IF is on restricting the feeding time-window, rather than restricting energy intake. IF consists of a combination of voluntary fasting (usually > 12 hours) and non-fasting (re-feeding) over a given period. The method that is receiving most attention from athletes is ‘time-restricted feeding’ (TRF), also known as the ‘16:8’ method. This method recommends fasting for 16 hours and shortening the duration of the daily eating window (during active daylight) to a maximum of 8 hours, without altering energy intake or diet quality. TRF can include food intake during the first half of the day (06:00 to14:00 = early time-restricted feeding [eTRF]) or during the second half of the day (12:00 to 20:00 = delayed time-restricted feeding [dTRF]). IF induces fat loss, and is an attractive weight loss option since only the time of food consumption is restricted (no calorie-counting or adhering to difficult diets). Eating according to circadian rhythm (during active hours of the day when the sun is up) has also shown to improve metabolism, blood sugar control, and cholesterol and triglyceride levels in overweight and obese individuals. It is important to note that most studies evaluating the effects of fasting on weight loss and athletic performance use different fasting regimes and protocols and vary in their outcomes. Data on athletes from the majority of studies are based on Ramadan data/overnight fasts that were < 12 h, with limited studies employing the TRF protocol (16:8 method). Although limited emerging evidence suggests that there may be a use for time-restricted feeding (combined with resistance training and high protein intake to preserve muscle mass and improve body composition), no performance benefit has yet been shown. |

During the past decade, knowledge about the specific role of protein to manipulate body composition and attain high-quality weight loss, has evolved considerably. Fat and carbohydrate (the body’s main fuel sources) intake needs to be carefully manipulated to create an energy deficit. But high-quality weight loss also requires adequate intake of high-quality protein distributed evenly and frequently in relation to exercise and recovery.39

• General considerations for weight loss and training40

- Athletes need to approach weight loss with care to prevent compromised training, muscle loss, risk of injury, illness, and overtraining syndrome.

- Changing body weight or composition should never compromise the energy intake needed to sustain performance. Carbohydrate intake should still match training requirements.

- Severe energy restrictions or weight loss practices in which one or more food groups are eliminated may put an athlete at risk for micronutrient (vitamins and minerals) deficiency.

- Losing weight gradually (0,5 kg or less per week) is ideal. Losing weight rapidly can compromise training, performance, and immunity, and cause muscle loss.

- Adjust protein intake to maintain muscle mass when restricting energy intake to enable fat loss (protein quantities between 1,6 and 2,4 g/kg body mass per day).

- In addition to high protein intake, athletes taking on high-quality weight loss may benefit from extra resistance exercise to preserve lean mass.

- Lose unwanted fat in the off-season when athletes are not competing.

• Practical considerations for weight loss and training12

- Athletes need to consume foods from all the food groups to take in at least the recommended daily allowances for all micronutrients.

- When restricting energy intake, restrict fat intake and focus on low-fat foods (i.e. low-fat or fat-free dairy products, lean meats, low-fat carbohydrate snacks).

- Make sure that you still eat enough carbohydrates to match training (do not restrict carbohydrates to less than 3 to 4 g/kg depending on training load). Limit added sugar and refined carbohydrates and focus on nutritious low-fat carbohydrate sources (e.g. wholegrain products, fruits and vegetables) with a higher fibre content to keep you fuller for longer.

- Make sure you eat enough protein and spread protein intake throughout the day. Consume a low-fat high-quality protein source (e.g. low-fat milk or dairy, lean meat, fish, chicken) as part of a meal or snack every three hours.

- Carefully plan the timing of your meals and snacks to ensure that carbohydrates are included before and after high-quality sessions for fuel and recovery.

- Recovery (refuel, repair and rehydrate) is very important after training, especially when trying to lose body fat. Include a high-quality protein source and sufficient carbohydrates in your recovery meal (refer to the section on post-exercise nutrition). Training can potentially be planned in such a way that the recovery meal also forms one of the main meals.

- The following general weight loss tips will also assist with weight loss: drink enough fluids, eat slowly, avoid alcohol, get enough sleep, try to reduce stress and record your portion sizes.

10.4 How can sports drinks support training or performance?

Sports drinks (carbohydrate energy drinks) can be very useful for athletes participating in high intensity or endurance sport, as it contains both carbohydrate for fuel and flavour and electrolytes (sodium) to help the body ‘hold on to’ fluid more effectively and also stimulate thirst. In fact, carbohydrate energy drinks are the best proven ergogenic aid. However, sports drinks – whether homemade or commercial – should only be consumed during activity as they are a high-energy source specifically formulated to fuel the active body.

- Fluid

The fluids that sports drinks provide during exercise are important to replace fluid losses, prevent dehydration and help cool the body. Flavourings encourage regular drinking.

- Carbohydrates

A 6% carbohydrate solution (6 g carbohydrate per 100 ml drink) strikes the optimal balance in taste, rapid fluid absorption and energy supply for working muscles. Undiluted juice or carbonated drinks should be avoided because they typically contain too much carbohydrate (10% to 12%) and may cause gastric discomfort and delay gastric emptying. Multiple carbohydrate sources are preferred because this helps stimulate fluid absorption.

- Electrolytes

The electrolyte content of a sports drink should attempt to replace both the potassium (30 mg/250 ml) and sodium lost through sweat. A potassium concentration of 30 mg/250 ml should be adequate. Sodium intake of approximately 100 mg/250 ml enhances the taste of a sports drink, facilitates the absorption of fluid and helps to maintain body fluids. Sodium may also stimulate voluntary drinking.

Homemade sports drink recipe 1

10 tablespoons sugar (120 g)

3/4 teaspoon salt (4,2 g)

1 package unsweetened powdered cold drink

Water to make up to a final volume of 2 ℓ

Per cup, the drink provides:

14,8 g carbohydrates (6%)

230 kJ energy

102 mg sodium

121 mg potassium

Homemade sports drink recipe 2

1/2 cup orange or berry juice (125 ml)

9 tablespoons sugar (110 g or 133 ml)

3/8 teaspoon salt (2,1 g or 2,1 ml)

1 package unsweetened powdered cold drink

Water to make up to a final volume of 2 ℓ

• Unnecessary ingredients in sports drinks

Ingredients other than fluid, carbohydrates and electrolytes are unnecessary in sports drinks because the body cannot use them during exercise.

- Herbs, e.g. guarana, gingko biloba, ephedra and ginseng, are often added to sports drinks but research shows no conclusive performance benefits. Experts question the benefits and safety of these herbal ingredients.

• What practical advice can athletes follow to ensure optimal benefit from sports drinks?

- Choose a sports drink with a 6% to 8% carbohydrate solution.

- Avoid unnecessary substances, e.g. herbs, vitamins, and minerals in sports drinks.

- Drink small amounts regularly during training (according to schedule or in all drink breaks provided).

- Avoid taking sports drinks outside activity periods.

- Monitor drinking hygiene. Athletes should each use their own water bottles and wash and rinse them thoroughly after use.

- Pack a favourite sports drink for training sessions and competitions.

Drink flavoured fluids through a straw to limit the amount of contact between the sports drink and teeth. This can reduce the risk of dental decay.

10.5 How should an athlete start a competition day?

Ideally, an athlete should start a competition day rested, relaxed, refuelled, and rehydrated. Try to get a good night’s sleep to ensure that you are rested, and plan and pack your cooler box the night before so that you can relax when it comes to your competition day nutrition (see the FAQ on ‘Is the food supplied at sports events recommended for athletes?’ for cooler box ideas). To ensure that you are fully refuelled and rehydrated before your competition event, you may also need to plan when and what you will be eating for breakfast on the competition day (e.g. if you need to get up very early to travel to the competition venue, you may need to eat on the run).

Nutritional guidelines for the competition day

- Eating on the day of a competition is important to prevent hunger before or during activity, to top up the liver glycogen stores after an overnight fast, and to help supply fuel to muscles.

- Breakfast is the most important meal of the day, especially on the day of a competition.

- Get up at least four hours before the competition. For example, if your first item or match is at 08:00, you should wake up at 04:00 and have breakfast not later than 05:00. If this is not possible, ensure that you eat a pre-event meal the night before and have a liquid meal or snack as soon as you have woken up (one to two hours before the competition). The same guidelines for pre-exercise meals and snacks apply to competition day. Refer to section ‘Intake before exercise’ for general guidelines and more pre-exercise snack ideas.

- Try to eat your normal breakfast before leaving home and remember to drink at least two cups of fluid with the meal.

Suitable breakfast options

|

- If you have to travel a long distance or need to make an early start before a game, pack an on-the-run breakfast.

On-the-run breakfast options

|

- In situations where nervousness or excitement decreases appetite, use meal replacements or flavoured milk as a liquid meal.

- Never experiment with something entirely new on competition day.

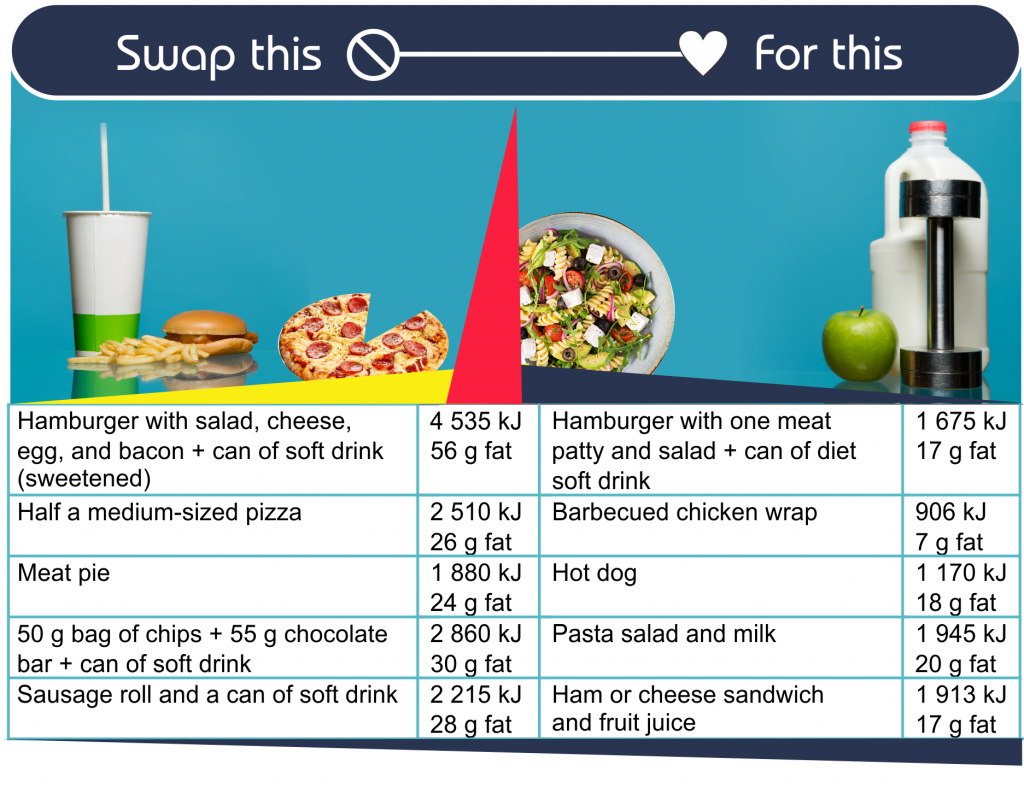

10.6 Can the food at sports events be recommended for athletes?

Food available from vendors at sports events (e.g. boerewors rolls, potato chips, chip sticks, and meat pies) is not ideal for athletes on competition days, as they are often high in fat and protein. Such foods take longer to digest.

If food has to be bought at the event, choose the options that will more likely support a gold medal performance!

Cooler box meal ideas

- A cereal or energy bar with fruit juice

- Crackers with cheese wedges and cordial

- A packet of popcorn or pretzels with a few biltong sticks and cordial

- A bread roll with peanut butter and a fruit

- Jaffles with lean mince

- Chicken wraps

- Homemade burgers

- Frozen fruit lollies made from blended ripe leftover fruits and 100% fruit juice

- Trail mix – a blend of unsalted nuts, seeds and dried fruits

- Melba toast with dips, e.g. avocado or low-fat cottage cheese

- Corn on the cob or tinned sweetcorn

Cooler box snack ideas

- Flavoured milk

- Drinking yoghurt

- Low-fat flavoured yoghurt

- Liquid meal replacement

- Drinking cereal

- Sports drinks or cordial

- Jelly sweets

- Water

- Sandwiches with jam or honey

- Fruit juice

- Fresh fruit

- Raisins

- A bread roll with banana

- Cereal bars

- Banana or date loaf or muffins

BUT THE BEST SOLUTION IS TO PLAN AND PACK!

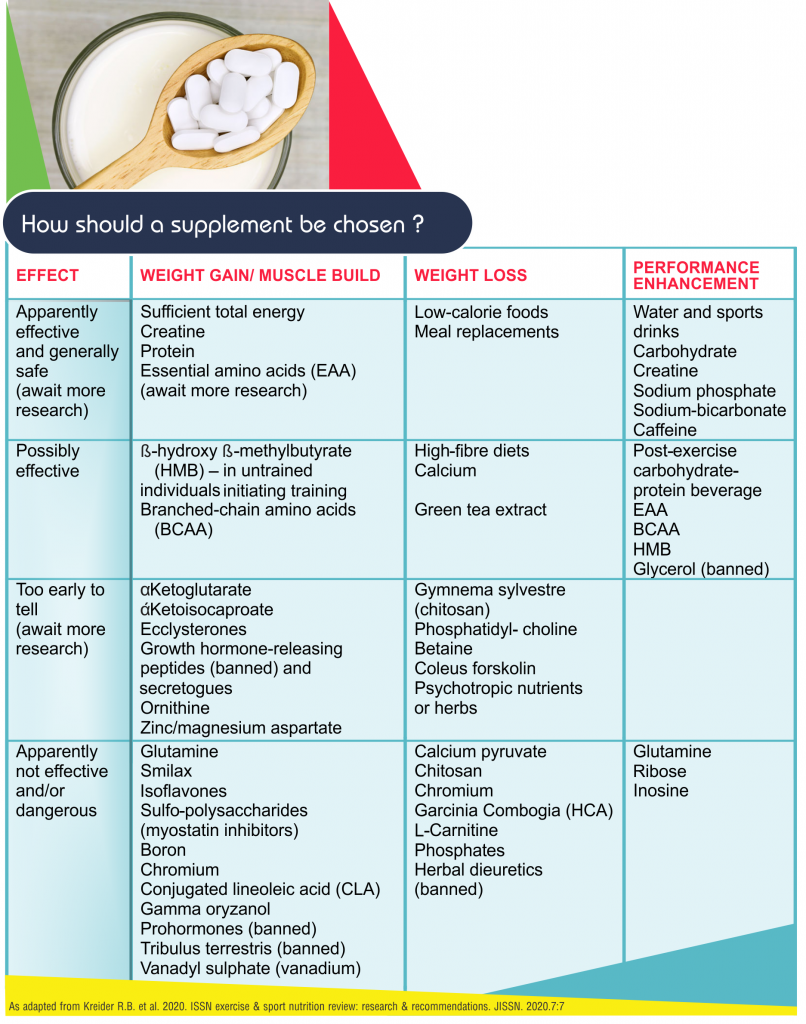

10.7 What about supplements?

Supplements are often marketed as ‘ergogenic aids’, and claim to improve strength or endurance, increase exercise efficiency, achieve a performance goal more quickly, and increase tolerance for more intense training. Dietary supplements come in a variety of forms, including tablets, capsules, liquids, powders, and bars. Many of these products contain numerous ingredients in varied combinations and amounts. Among the more common ingredients are amino acids, protein, creatine, and caffeine, but can also include herbal ingredients, stimulants, hormone precursors and many more.30

• Why athletes use supplements

As training programmes become more demanding, the role of nutrition becomes more important to sustain good performance. A varied diet that meets the energy needs of a training athlete should provide all the essential nutrients in adequate amounts to ensure optimal adaptation to training and performance. Athletes should therefore ensure that they have a good diet before contemplating supplement use.

However, over the years a culture has developed which believes that supplements can in some way compensate for poor food choices and the increased stresses of modern life. Supplements are often used:

- to compensate for an inadequate diet

- to meet abnormal demands of hard training or frequent competition

- to boost performance

- to keep up with teammates or opponents

- on recommendation of a coach, parent or other influential individuals.

The benefit of most supplements is still inconclusive and often not scientifically proven. Individuals respond to and tolerate supplements differently and some can experience a placebo effect.30

• Are supplements regulated in South Africa?

There is no governing body to control or regulate the production, distribution or marketing of sports supplements in South Africa. Therefore, there is no way to ensure their safety or efficacy and products can be marketed with very little control over the claims and messages they provide – a situation of which many companies take full advantage.

According to the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), ‘most supplement manufacturers make claims about their products that are not backed by valid scientific research, and they rarely advise the consumer about potential adverse effects. The supplement industry is a money-making venture and athletes should get proper help to distinguish marketing strategies from reality.’

Supplements are big business. Athletes are often drawn by the images of picture-perfect bodies and the promise of enhanced performance or recovery by a certain product. Yet, there are many potential risks and little or no benefit.(31)

• What do supplements contain?

Many dietary supplements contain multiple ingredients. However, much of the research has focused only on single ingredients. One therefore cannot know or predict the effects and safety of single ingredients in combinations. The amounts of ingredients may vary among products and sometimes the products contain proprietary blends of ingredients without stating the amounts of each ingredient in the blend.30

Safety considerations

Supplements can have side effects and may interact with prescription and over-the-counter medications. In some cases, the active constituents of botanical or other ingredients present are unknown. Many supplements that contain multiple ingredients have not been adequately tested in combination with one another.30 Supplements can also be contaminated by anabolic steroids and other prohibited stimulants. This means that an athlete’s use of a sports supplement may lead to a doping test turning out to be positive.32

The sensible approach30

- Athletes are advised to follow a ‘food first’ approach to avoid using supplements that aren’t needed or could result in nutrient intakes that are too high.30,33

- When using supplements, use them in addition to a carefully chosen diet.

- When considering the use of supplements, athletes will need to weigh the potential benefits with the possible negative impacts, such as negative effects on general health or performance, risk of accidental doping or risks of consuming toxic levels of substances.33

- There is no justification for the use of supplements by young athletes.32

- People interested in taking dietary supplements to enhance their exercise and athletic performance should talk to their healthcare providers about the use of these products.30

• What should athletes know about different supplements?

Sports drinks – carbohydrate-rich solutions

Sports drinks are aimed at fluid and fuel delivery during exercise. In general, a sports drink that is used during exercise should contain carbohydrates (6% to 8%), sodium (20 to 30 mmol/ℓ) and potassium (3 to 5 mmol/ℓ). The recommendation for intake should consider the climate situation (cold or hot environment), the individual carbohydrate and fluid need of the athlete and the athlete’s tolerance for the drink. Sports drinks may be beneficial to athletes doing high-intensity exercise, endurance events, prolonged intermittent exercise or weight class sport for quick recovery.

Sports gels and sports or energy bars – carbohydrate-rich sport food

Sports gels and sports or energy bars are a compact way of consuming a variety of nutrients and can be very useful to busy athletes. Solid bars are better as they provide more nutrients than energy drinks. It is important to consume these products together with adequate fluids to meet hydration needs and to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal intolerance.33

Protein and protein components

Athletes with a high protein need can use protein-rich food sources such as dairy products, meat, fish, eggs and soya. The intake of supplemental protein when the diet is already sufficient in protein will probably have no additional benefit for the athlete. There is also little supporting evidence that supplements with individual amino acids can benefit athletes who are following an adequate diet. Some athletes, however, find it difficult to consume protein food sources at the ideal time and a protein supplement may be convenient. Athletes should be aware of protein supplements that contain extra ingredients and impurities.

Amino acids are individual components of protein molecules and are sold with promises of superior functioning. However, most amino acids are found in abundance in food sources, making supplementation unnecessary and expensive.

Vitamins and minerals

Official recommendations for the vitamin and mineral intake for athletes do not exist, but it is generally accepted that athletes need more than sedentary people. These nutrients are best supplied through a varied diet based on nutrient-rich food. In athletes who restrict energy intake or when there is a limited food supply, a multivitamin-mineral supplement might be helpful. There is no justification for taking extra vitamin supplements. There is very little evidence to suggest that extra vitamins and minerals will benefit athletes who do not present with a deficiency.33

Caffeine

Caffeine is a legal and known stimulant. Athletes have used caffeine to enhance performance for decades. Known side effects are irritability, nervousness, increased heart rate, headaches, and loss of sleep. If you are not a regular caffeine user it would be wise not to start, as it can be very addictive.14

Creatine

Creatine is found naturally in skeletal muscle tissue and liberates adenosine triphosphate (ATP) for brief high-intensity exercise. The human body can make creatine from amino acids that become available after the digestion of protein. Creatine is also found in food sources, with meat and fish being the richest natural sources of creatine. As a supplement, creatine is available in powder, liquid, and capsule form. Creatine supplements have become popular among competitive athletes in an attempt to enhance energy production, increase the body’s ability to maintain force and delay fatigue. However, products containing creatine do not work by themselves; instead, they help athletes maximise their training or performance only because of the improvement in recovery time. Strength and muscle mass changes associated with creatine use therefore occur because athletes are able to do more work but with less fatigue in a specific period of time.

Creatine supplementation has been shown to be most beneficial in repeated bouts of high-intensity exercise, separated by short recovery intervals. However, not all studies have shown that creatine improves athletic performance or that everyone responds the same way to creatine supplements. People who tend to have naturally high stores of creatine in their muscles don’t get an energy-boosting effect from extra creatine.

At present, creatine seems relatively safe for use with minimal to no side effects if taken as directed. Failure to do so may negate its proposed benefit or even lead to decreased performance because of intestinal distress.14,32

Creatine as a supplement has been studied for short-term use only. Although creatine is not banned by the International Olympic Committee, using it for athletic performance is controversial, because:

- the long-term consequences of creatine use or the effect of overdosing is unknown;

- there have been anecdotal reports of an increased risk of muscle cramps, strains and tears;

- there is concern over kidney complications;

- there are no data on the effects of creatine supplementation on other organs that store creatine (i.e. heart, liver, brain); and

- supplements have a high risk of being mislabelled or contaminated with banned substances.14,32,34

Are creatine supplements safe for young athletes?

There is concern over the marketing of creatine-containing supplements to teens since neither safety nor effectiveness in persons younger than 18 have yet been tested. The efficacy of creatine supplementation in children and adolescents is questioned for the following reasons:

- Children and adolescents rely more on aerobic than anaerobic metabolism. The goal of creatine supplementation is to enhance anaerobic metabolism. Supplementation in children and adolescents would therefore have a limited effect.

- Adolescents appear to be able to regenerate high-energy phosphate during high-intensity exercise and improve performance in short-term, high-intensity exercise through training. The need for supplementation is therefore reduced. Performance during growth tends to be limited by mechanical factors rather than by the relative contribution of the aerobic and anaerobic energy systems.

Creatine supplements are therefore not recommended for children or adolescents.

Factors such as optimal training, sufficient rest and sleep, good nutrition, the right equipment and the correct mental attitude will produce much larger performance gains than any supplement. Any athlete will improve their performance by focusing on these basics, rather than relying on a ‘quick fix’ that most probably doesn’t work or has potentially adverse effects.14

Can sport supplements benefit young athletes?